There’s a thing that I’m sure is going to come up in the Tuesday Night Writing Club. Wait, I haven’t said what that is.

Briefly, it’s a new five-week writing workshop I’m running from next week. Each Tuesday evening from 19:00-21:00 (UK time), the first hour is full-on writing exercises and challenges. Then the second hour is us talking through what we’re writing, what we want to write –– and why we’re not writing it.

There are ten of us but I would like a couple more. If you’re reading this in time, take a look at the Eventbrite page.

Anyway, I don’t know what we’ll end up talking about and of course that is one of the reasons I’m so looking forward to it. However, wherever three or more writers shalt meet, so typically there will come up this certain point that’s been on my mind.

Usually it’s a new writer who says this, but it can be an old one who’s just jaded. Whichever it is, they’ve decided that they must now write the next Harry Potter, the next Twilight, the next 50 Shades, the next insert-latest-hit-book-or-show here.

You can see why they’d think this. Plus it doesn’t hurt that people who aren’t writers assume both that this is what we have to do and that it is what we want to do.

Except the answer is no. There’s a term I know from technology but I have a tiny little reason to suspect may possibly have originated in some sport or other. Don’t skate to where the puck is, skate to where it is going to be.

If you see that dramas about chess are in, don’t write one. Because by the time you’ve even finished writing, let alone got it through production, dramas about chess are old news. Chess, Westerns, everything changes. Except zombie films. For some reason that genre just will not die.

I think that this is obvious and that even if you were worrying about writing something like, I don’t know, the next Line of Duty, you soon see that it’s obvious. Quite clearly, there is no point emulating anything, you must write something new, something you want to write.

And since the emulation never works, you might as well write something new anyway.

Only, for exactly as long as I’ve been thinking this about topics and genres and characters, I’ve been wrongly rigid about everything else. You may want to write a sprawling 100-hour fantasy, I thought, but you’ll never get it on because there is no slot for 100 hours.

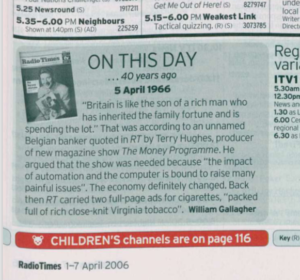

Television drama has to be one hour long, I thought. There are exceptions, like the two-hour crime series that Inspector Morse made popular. And television comedy has to be half an hour.

Hand on heart, I still think that should be true, I just know that it technically doesn’t. Take a look at any one-hour drama on Netflix and you’ll see that the episode length varies enormously. Or I can’t remember which episode it is now, but there was a Doctor Who which came out as over 60 minutes in the edit and BBC Wales had to make a case to BBC1 why it should be allowed. And why it should be allowed to mean the rest of the Saturday night schedule should shuffle along.

Curiously, if Doctor Who had aired on a weeknight then, there wouldn’t have been any discussion. BBC1 has to hit the Ten O’Clock news, not the Five Past Ten one. So there are still technical limits.

I do just also think that there are writing ones. I realise that we’ve all been trained to expect sitcoms to be thirty minutes, but when they’re not, you can usually tell. Amazon Prime UK has extended versions of some Parks and Recreation episodes and I could not tell you which ones are longer because it all works so well.

But then I think it was Arrested Development that let its regular episodes stretch out a bit once it was on a streaming service, and there you knew. There you knew the episodes felt flabby. Time constraints are important for writing.

The reason every bit of this is on my mind now, though, is because another set-in-stone technical issue appears to have vanished. For as long as I can think, television would not do anthology series, just would not do them.

You’re thinking of The Twilight Zone, but remember how long ago that was. For a mixture of practical and marketing reasons, it’s not been viable to make anthologies. The practical being that a season of separate stories –– entirely separate casts, sets and locations –– is gigantically more expensive than one following the same characters.

And then the marketing one is that viewers like to follow the same characters. I do. I like coming back to spend more time with characters I like.

It was so certain that anthologies were a thing of the past that in the 1980s, Don Bellisario devised Quantum Leap as a trick. Its leading man “leaps” into the bodies of different people in every episode because this is really an anthology in disguise.

That was in the days when network television existed and when network television was extremely profitable. Today it isn’t, so naturally more expensive shows just aren’t getting made.

Except they are. And anthologies are.

Amazon Prime commissioned Modern Love in 2019 and I’ve just finished watching the eight episodes because I’ve been savouring each one, letting each one linger. It is the anti-binge show, the one you do want to race through, but you also want to hold on to.

I utterly relish that anthology and it doesn’t hold back on the expense.

I have no idea how we ended up with big bucks network television fading away. Or how we cope now with every new show competing not with whatever else is airing at the same time, but with a hundred thousand other shows and channels and entire streaming platforms.

But if it gets us Modern Love, I’m in. There are plenty of shows I’d like to write for, but I yearn to be good enough to write Modern Love.