I should have seen this one coming. Usually if someone changes my mind about something, they do it quickly and I can never see things the way I did a moment before. This time, this week, that did happen, but it was less a new idea, more a confirmation of what I now realise I’d been working towards.

Previously… I used to believe that a story idea belonged in the form you first thought of it. If you thought of a radio play idea, then trying to do it as a novel was contorting it. It was contrived, it was wrong. The idea, the story, and the form are all part of the same thing, I believed, and if you change any part, you are going against the grain of the whole. If you want a TV idea, go think of one, don’t distort a stage story.

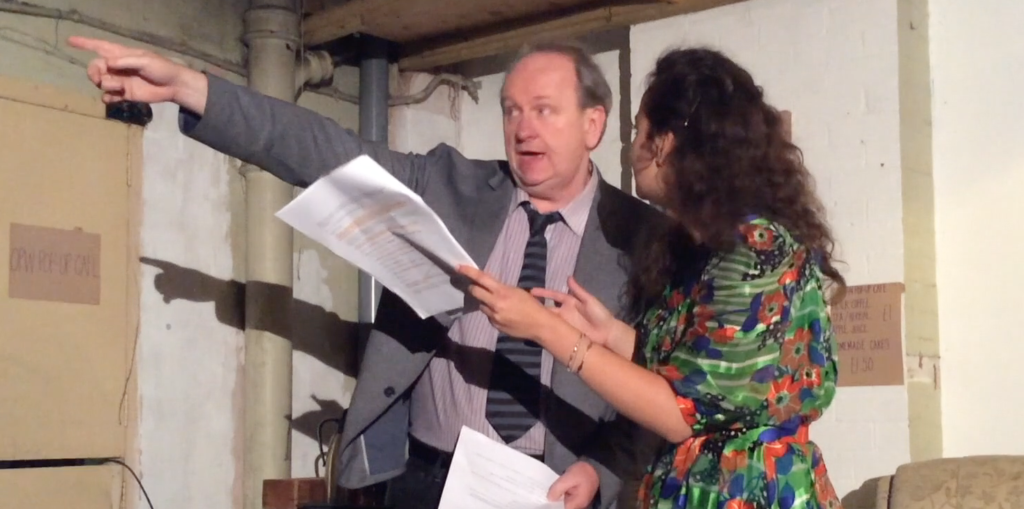

The person who changed my mind this week didn’t listen to all of that and then conclude that I was talking bollocks. But she did disagree and she did point out why.

And I was left with nothing else to say but the truth: “Then I’m wrong, aren’t I?”

I don’t want to let go of the opinion entirely, except I do. Maybe I just want to hang on to how I think the medium is important.

This woman’s entirely persuasive examples were centred on dramatisations of books and how interesting it is to see the process of bringing something to a different form, of how it naturally brings out other aspects, how it gives other opportunities. The example I gave back to her was the same. Slow Horses is better on television than it is in the original books. Screenwriters Will Smith, Morwenna Banks and co haven’t lost any of the strengths of the novels, haven’t changed anything, but have made it richer somehow.

But then five years ago I had a chance to do a short stage version of a radio play that I’d been struggling with. Struggling so much that actually I only finished it last month. Central to the many problems was a certain point where I needed one character to encourage another, but they physically and literally cannot meet. I think my ultimate solution in the radio script is a bit of a fudge, but for stage, I just had one of them walk by the other and whisper.

Didn’t matter that it was physically impossible in terms of the plot. It was right. The stage format allowed me to let that happen and it was right.

Similarly, I have a new stage play that comes from a TV idea and theatre lets me do things television never could. That story must start simultaneously in two time periods and for TV, I’ve made one winter and one summer to give it a visual start to the difference, before you then separately piece together just how many years apart they are.

For theatre, I put my characters on a train and had a train guard announcing to one “arriving London, 1987”, and to the other “next stop, Hull, 2019.”

“Seems a long journey,” says one of my characters.

“Try doing it standing up,” says the guard.

A small warm exchange and a simple, direct telling the audience what’s going on, but also done in a way that gives you a flavour of what’s coming next. Using an aspect of theatre that is pure stagecraft, that would be out of place on radio, out of joint on television. Using the form the story is being told in.

Sometimes you can still be contorting and contriving as you move between forms. But now I think the medium is only part of the message.