Some 19 years ago in the last week of January, 2004, I spent an entire afternoon sitting alone in a Radio Times studio in London while BBC Radio stations took turns calling me. Back then, they were calling over a broadcast-quality ISDN line and while I can’t remember how many stations there were, my job was to be on a show talking about Radio Times.

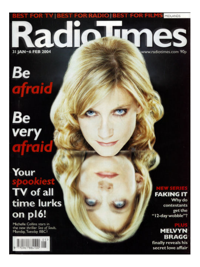

Specifically, RT that week had one of those countdown features, this time the Top Ten Spookiest Shows Ever or something like that. I presume I had worked on the feature, I know I was the only one available that day, but it’s all a bit fuzzy. I’ve just spent a quite happy 20 minutes Googling to find the barely-remembered cover.

Flash forward to this week and on Tuesday I got to do it again, from my Birmingham office and over FaceTime audio. Two decades later, I am clearly the man in demand. But it felt like I was that day because 11 BBC Local Radio stations and 1 BBC national station wanted my opinion about the return of Fawlty Towers.

Flash forward to this week and on Tuesday I got to do it again, from my Birmingham office and over FaceTime audio. Two decades later, I am clearly the man in demand. But it felt like I was that day because 11 BBC Local Radio stations and 1 BBC national station wanted my opinion about the return of Fawlty Towers.

Hang on. Not true. They wanted someone’s opinion, they each wanted a way to talk about this news, to get their listeners talking about it, and they wanted an extra voice in the mix. I am nothing if not an extra voice and I don’t care how I ended up getting to do this, I got to do it and I relished it.

So that’s very nice for me and also it’s not as if I believe my opinion has any particular value. Yet it looks very strongly like I’m going to give it to you anyway.

And yes, here it comes. If the question is whether Fawlty Towers should come back, the answer is there is not one single pixel of a chance you can possibly guess until it’s made – but that won’t stop us talking about it until, in my case anyway, we get sore throats.

Really the only key thing, I thought, was over the issue that it appears Connie Booth is not involved. She and John Cleese wrote the original, I’ve read the scripts, she’s tremendous and seemingly she isn’t writing this one.

Other than that, what I realised from saying this stuff over and over is why the announcement was made now. There are practically no details, certainly not any indication of where the new Fawlty Towers will be screened – and that’s why it was announced this week.

The makers are shopping this show around the networks and the streamers, and they are now able to point to the mass of attention the news got. There is public interest, there is public demand, this show is guaranteed to get high ratings. That’s what they will be saying to the streamers and they are right.

For episode 1.

Everyone will watch the first episode of a new Fawlty Towers, it’s then up to the show to keep us coming back.

Apparently last year there were 599 new scripted comedy and dramas on American television alone. That’s an unimaginable number and, possibly more significantly, an unwatchable one. You and I will never even hear of most of those shows and simply getting our attention at all must be murderously difficult.

Fawlty Towers got our attention instantly.

I think that is why shows are brought back, because they have a built-in audience and it’s sufficiently big that the return is also brought to the attention of new audiences.

Only, I do think shows finish for a reason. They do come to an end, they do often fizzle away. To work anew, they have to become a new show.

And I don’t think we want that. What we really want, always, is not a sequel, not a continuation. We want the first one again, we want to be back when we hadn’t seen that first one yet and it was all to come. We want to recapture whatever it was we were as well as what the show is.

It’s impossible for a show to live up to how we remember a beloved original, decades after it ended.

But it can be better. All that time ago in 2004, we had no idea that it would be just the next year when Doctor Who would be back and not just living up to the original, but exceeding it.

I’m trying to see from your face whether you recognise any of that, but all I can see is that you’re looking a lot younger than me. I will try to still like you.

I’m trying to see from your face whether you recognise any of that, but all I can see is that you’re looking a lot younger than me. I will try to still like you.