I already miss the BBC’s now-cancelled Holby City show, but chiefly in the way I’ve been missing this hospital series each week for two decades. It’s a soap and those just don’t hold me, so I’m not a viewer, I’ve no concern about it being ended so abruptly. I have a lot of concern for its writers, and all its cast and crew, but – sorry – I’m not going to notice when it’s over.

Except I do feel I owe it something.

Holby City is not the cause of my realising it’s better to write television drama than it ever is to write about television drama, but it was one key pixel in that realisation because of what happened at its launch, some 22 years ago now.

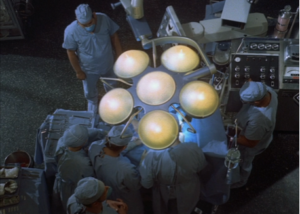

I don’t know if this is still the case, but back then the BBC had gutted one floor of its office building in Elstree and turned it into this Holby City hospital. It was slightly surreal, I was used to going up in that lift and stepping out to see various people in their various offices, now you step out into a ward. I remember being very impressed with the thoroughness of it all, with how it was immediately obvious you could shoot from any angle you needed and there would be little or no time lost setting up anything.

What I don’t remember is how it was lit. I’m sitting here, talking to you, fully able to walk around that set in my head but not able to make myself look up to its ceiling. I don’t remember noticing a ceiling full of lights, but I may just have not noticed.

I will have been impressed by the set and to this day I remain impressed by set designers and dressers. I will also have been impressed by the ten or so other media journalists I was with, though in that case I’m not still impressed. Inside of twenty minutes, I felt I’d gone native: I was rooting for these television drama people and I was embarrassed by the journalists.

Sometimes you pick sides, sometimes the sides pick you.

So there I was – nuts, I can’t remember if I were there on behalf of BBC Ceefax, BBC News Online, or Radio Times. It was one of them, anyway, and we were shown around the ward, then seated for the group interviews.

Ten journalists or so, seated in a semi-circle on the ward, with each main actor being popped down in front of us in turn.

What I most clearly recall is George Irving, who played a grumpy surgeon on the show when it started. First journalist asks: “Did you ever want to be a surgeon in real life?” He gives them a nice quote, saying no, but talking about how inspiring surgeons are.

Next journalist: “when you were a child, did you dream of being a surgeon?” He found some different way to answer.

Third journalist: “Would you have liked to be a surgeon?”

Then it was me and I do remain proud of this. I asked him whether he felt it was going to be hard sustaining his curmudgeonly character over a long series and without it becoming repetitive. Of course he said no, but what I can picture now is how he uncrossed his legs, sat forward, visibly thought about his answer, and told me something of his process and a hint of how they had plans for the character.

Fifth journalist: “When a child you were, a surgeon did you want to be?”

He sits back, re-crosses his legs, gives a quote about how inspiring surgeons are. I’m sure it was hard for each actor to sit there in their turn, facing all these faces, but I’m equally sure that they didn’t need to think hard about their answers, most of the time.

For I want to tell you that nine of the ten of us asked about bloody surgeons and I’m pretty sure I’m right. But I can’t come up with another five variations on that question.

There was another actor who got nine identikit questions from everyone and I know that’s everyone except me, but I can’t remember what I asked her. What I know is that because she was a woman, her questions were all about her relationship with someone. Apparently everyone knew she’d just broken up with somebody or other and that was crucial to the coverage of this new soap.

For some reason, and truly who knows why, I got to do a separate interview with her afterwards. That might be why I don’t remember my question in the semi-circle, I may not have got to ask anything there because it had been arranged that I would get ten minutes with her afterwards. Cannot remember why. Completely blanked. Come on, it’s near as dammit a quarter of a century ago.

But I can still see her to my left as we walked away from that semi-circle and over to a quiet part of the set. I’m not sure how I phrased it, but on the way I know I basically said that I hoped she was okay after this apparently incredible break up but –– I don’t think I said this rudely –– I wasn’t interested. I was interested in the show, in the character, in the drama. Wasn’t sure why the others were so obsessed.

“I know, right?” she exploded. It was deeply flattering, like what I’d said was a pinprick that burst a balloon and she now knew she could say what she really thought. “Who the fuck cares about my break up?” she said. I couldn’t now tell you anything else she said in the actual interview, I haven’t a clue what I wrote, but I liked her hugely and you would too.

You’ve noticed that I haven’t said her name, though. I’ve just got an odd sense that saying it would be bringing up the relationship, whatever it was, or that she might not appreciate my quoting an off the record remark. All these years later, I cannot tell you an off the record remark and who said it. I’m clearly being professional and it is not that for some reason today I’ve I’ve entirely forgotten her name.

I could look it up, I know I’d find her quickly. But then I could probably look up what I wrote and I don’t want to go there. I may still do a lot of feature writing on different topics, and I may even still do some media writing, but I’m not who I was back in, er, 1999 or whenever.

And that day on the Holby City sets was part of changing me, of making me choose a side. Which is why, if I weren’t already, I was then often on the wrong side of moods at places like Radio Times. Much as I loved RT, there would so often be times at RT and at BBC News Online when people there were frustrated that they weren’t being told something key about a new drama.

Whereas I would be right there in the same spot saying no, don’t tell me anything, hide things, lie to me, do whatever you can to make the drama surprising and compelling. I did then and do now despise soap magazines that splash headlines like “Shock Pregnancy” or “I killed him!” before those things happen in their shows. The magazines are told this stuff in advance, knowing it will be featured, because it’s believed that it builds excitement for the show and I think it does the opposite. You don’t have to watch anymore, so you don’t.

I said soaps can’t seem to hold me but there was a trial in Coronation Street once. Big thing, national interest, I want to say Deirdre Barlow. Not sure. But even though I don’t follow that soap, like millions of other people, I was drawn in to watching it because of this story of an innocent woman on trial over some false accusation. Until the producers said publicly that they would never let an innocent character go to prison.

Oh.

Screw that, then, what’s on the other channel?

That was another pixel in the picture, I realise now. It wasn’t one where I was on the side of the show, but was where I knew very clearly what drama meant to me and how revealing something early destroys it. It was one where I had very clear and strong drama opinions. It was also where I found again that there is this difference between soap and drama, plus which side of that I wanted to be on.

But at risk of going further away from Holby City, I’ve also realised that I can vividly see the real moment when I knew where my heart lives. Again, I should be able to work out the date really easily and I daren’t, but what I see when I close my eyes is where I was sitting in a BBC newsroom, this time definitely working for Radio Times.

I can see all the people around me, all the equipment, I can hear the sound of that huge room and feel that chair I was sitting in. And I can see the book I’m reading. The Writer’s Tale by Russell T Davies and Benjamin Cook – who was a Radio Times writer too – which was about the making of Doctor Who.

The book is a quite an incredibly intense read which, in its first edition, included scripts and drafts of scripts from the series. (Which reminds me: I’ve now read 1,928 scripts in my at-least-one-per-day lark. I should re-read some Doctor Who ones.)

But the majority of the book is an email conversation between its two authors. Which means every few paragraphs, you get a typical email heading with the subject –– plus the date and time.

I’m reading the book and there’s a bit I recognise. Some big decision being made about a particular character in the show and I was actually pleased in that moment, because I remembered writing about that decision for RadioTimes.com.

And then I noticed the date on the email.

Whatever it was, I knew immediately that it was pretty much precisely one year before I’d written my breaking news story about it on Radio Times.

And that’s when I knew. I’m not there yet, not even all these years later, but in that moment I knew I wanted to be making the drama decisions instead of writing about them an entire year after the fact.

Of course it helps that Radio Times, BBC Ceefax and BBC News Online later chucked me out but even if they hadn’t, I’d started down a road that would’ve seen me leave anyway.

And yes, it’s chiefly because of Doctor Who and that one single email.

But it’s also because of Holby City and my one single day on that show’s sets. I won’t miss the show as a viewer because I simply never got into watching it, but I do owe it something.