This is a claim that going around the internet again and I think that if you and I get together, we can stop it. Are you game?

It’s about writing scripts and an insistence that film and TV companies will judge your screenplay on its first ten pages. More, the claim is that this is wrong, it is unfair and even that it is distorting how people write.

So far as I can tell, only the BBC “No Apostrophes Please, We’re British” Writersroom directly states that its readers will judge on the first ten pages. The BBC Writersroom has a brilliant online collection of scripts, albeit not searchable, but otherwise doesn’t matter.

Still, the claim persists and my problems are with this idea that it’s unfair to judge on the opening ten pages and it’s wrong how this is affecting the way people write.

The argument over the unfairness is always that you can’t tell if a script is good until you’ve read the whole thing.

And actually, yep, you can.

If a writer thinks they’re able to make a script brilliant from page 80 onwards but doesn’t see that the first 79 are crap, they are not able to make any of the pages brilliant at all.

Let me put it this way. I long to live in a beautiful New York apartment building called 56 Leonard and of course if I had $40m I’d spend it on the penthouse. But as utterly wonderful as that apartment is, the penthouse is on the 57th floor and it needs 56 pretty solid floors below it.

Then there’s this bit that sounds more sophisticated: that the demand for a great opening ten pages means writers have to put action and jeopardy and comedy in there. That they can never build up to things, they can never do some kind of pure writing. I’m fuzzy on that last bit.

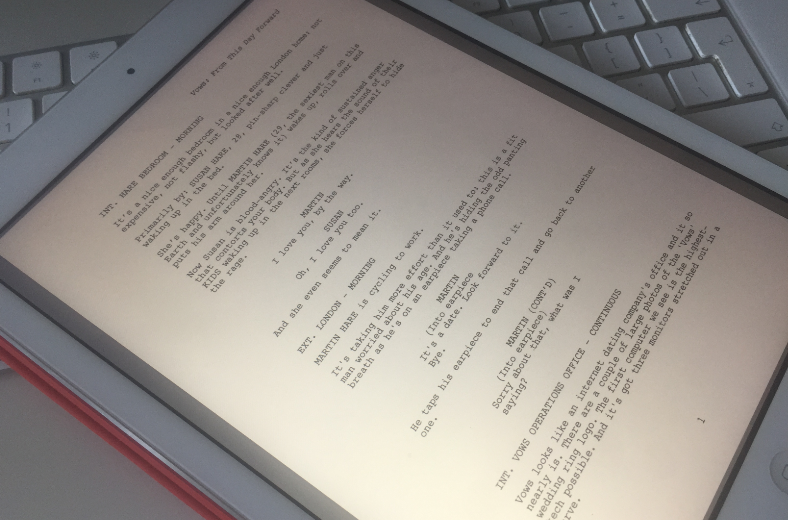

It is true that I recently changed the opening of a script of mine before sending it to a producer. The script had begun with something mildly gentle as we followed a character going in to work. And what I changed was that I added a new scene before it.

Only, I didn’t do that to hook the producer with a teaser.

The scene I added was, if anything, quieter than the going to work one. And I’ve just checked: it was slightly less than half a page

But it focused on another character. She was always my favourite, she was always the reason for the entire story yet initially I’d held back introducing her. I think I still do, really, but having this tiny scene open on her changes how you read the rest of the script.

What I didn’t do was move up the calamitous situation she gets into or add in an explosion or something.

It did used to be that in television you needed to have something big at the start to stop people switching over. Whereas in film, the idea was that people had paid to sit there in that room and so they’d give you at least a little longer. Film could therefore be a bit more slow and seductive where TV had to be smash/bang/grab.

I think that line has blurred to the point of invisibility: films are seen more on Netflix than in their run in the cinema, for one thing. Television drama has never been better than it is now with its ability to draw you in slowly and deeply and richly.

I get annoyed at the ten pages rule for all sorts of reasons but one of them is that there is no such rule so the whole thing is bollocks. Another is that the same people who trot out a rule about TV needing to grab the audience’s attention are the ones who think it’s unfair to judge a script on the opening. A reader is no more likely to slog to the end than a viewer is to sit there for two hours hoping the ending will be good.

Drama needs something at the start to make you want to watch further. It just doesn’t have to be something big, doesn’t have to be action, doesn’t have to be suspense. It just has to be something that doesn’t stop people reading on. Character, that’s my favourite. Atmosphere, that’s a good one too.

Even in this day of being able to switch to another of the million different dramas available on demand, your audience and the producer reading your script want to like what you’ve done. They want to enjoy this. They come in on your side and you can win them over in the long run but initially your job is to not lose them.

And I’m sorry, but it doesn’t take ten pages to lose me. It doesn’t take ten pages for me to know a script is poor.

It takes one. At most.

True, you can’t tell from the first page just how much you’re going to like the script but you can tell if you’re going to dislike it.

I’ve read 180 scripts this year and every time you know right away. You know when you’re in good hands, you know when it’s going to work. You don’t know if it’s going to be to your taste or interest, but you know that the writer is good.

So if you read someone saying the first ten pages are crucial then they’re probably trying to sell you a course. If you read them saying this and also that it’s unfair, they’re rubbish.

If someone tells you that you have to have a murder on the first page, nod politely and walk away.

And maybe there is one rule I can get behind. It’s the rule I’ve just made up where if someone insists their script needs 79 pages to get going, do whatever you like but don’t offer to read it.