I’ve been having trouble with a script I’m writing. It is partly because I appear to be in it and while my cold writer’s head can see that’s necessary to tell this particular story, even I wouldn’t watch something about me.

But then there is also this. The script is about real people. I am a real person, I’m a real person who hasn’t had breakfast yet and is having difficulty remembering whether he’s shaved this fuzzy morning, but I don’t interest me. Beyond wondering why I’m writing my own dialogue, and then why I’m reading it back, I don’t concern me. Instead, it’s everyone else I’m worried about.

I have more research about the two other real people in the story than is even really feasible. Plus above all the facts and the documentation, they were my friends. No question, I’m armed and ready in that sense, but I’m a writer who’s also a journalist: I would give up an eye faster than I would make up a quote for a real person.

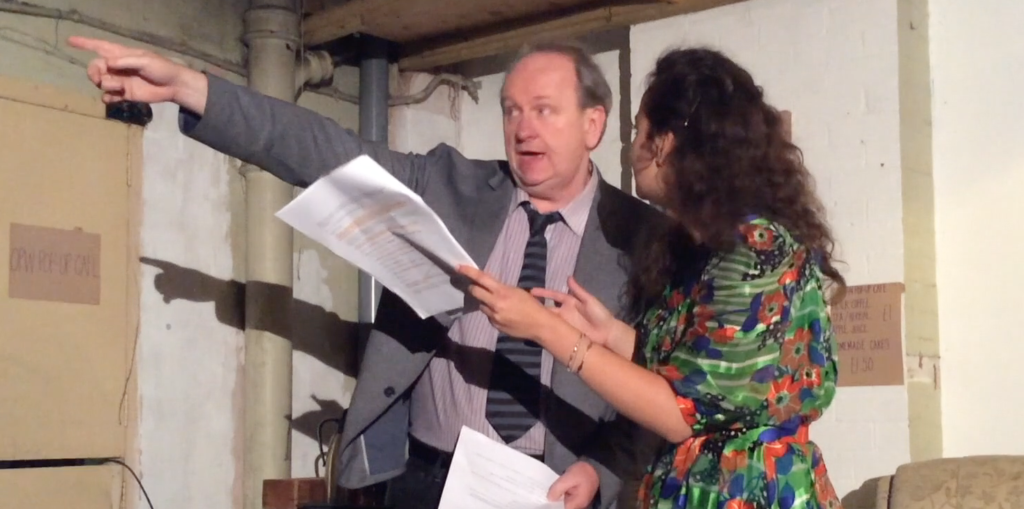

And now I’m going to have to make up entire speeches. Ouch, that’s revealing: I’m hiding in tenses and presumably because I am tense. The truth is that I already have made up entire speeches. I’ve written a two-page argument between me and one of these people. And that fight cuts into me, it hurts me, yet still I look at the page thinking he didn’t say that and nobody cares what I didn’t say back.

Except I had a dream the other night in which the late Alan Plater told me, in these precise words, “as long as it’s true, make it up”.

Then it’s like I planned what happened next. The reason I’m telling you this today, apart from how it’s pressing on my mind and I tell you everything, is that a play of Alan’s is to be re-staged at the Hampstead Theatre in London later this year. “Peggy for You” is about Alan’s first agent, Peggy Ramsay, and I read the script last night. Re-read: my copy of the published script turns out to be 21 years old.

It also turns out to be the true story of this eye-poppingly wild and wonderful woman, except it isn’t true at all. Except it is. It is an account of one day of her working life in the 1960s, completely made up, and therefore completely true.

I know because Alan’s introduction to the script says so.

“When I started writing the play, I heard her voice saying: ‘Just make sure it’s a pack of lies, dear.’ And it is. I did no research, but relied totally on a blend of memory, anecdote, myth and legend. The few elements that can be clearly identified could not possibly have happened on the day in question.”

Since Alan is one of the real people in my script, I think I should keep listening to him.