My first book was about the television drama “The Beiderbecke Affair” and it was for the British Film Institute. It was in their range of TV Classics and naturally, when you’ve done one, the only thing more likely than the publisher asking if you’d like to do another, is you asking the publisher if you can.

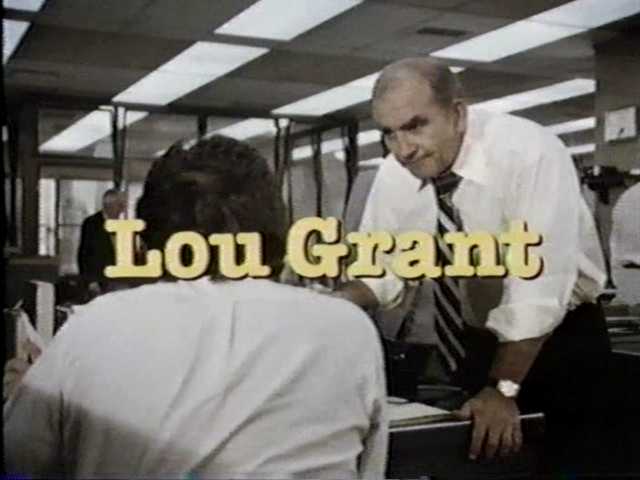

Even more than Beiderbecke, I wanted to write about “Lou Grant”. It didn’t fly and it didn’t fly for a dozen reasons from how the range almost never did US shows, to how the range wasn’t making money. But to make a pitch, I had to do a little bit of research.

That’s chiefly because if you are a publisher and you go to check whether there’s already a book on the proposed subject, you very quickly find that there is. My job was not only to convince the BFI that the topic was of value and that the chance of anyone buying a copy was good, but also that there was a reason for anyone else to do another book about this show.

To my mind, that was damn easy. This 1990s book about the making of “Lou Grant” is really an academic treatise. It sets out to explore whether the show and its “Los Angeles Tribune” newspaper setting was an accurate representation of real journalism at the time. The answer is: more than most. I’ve just saved you reading the book, although I’m denying you some fantastic access the writer had to key people involved.

As part of my own little initial stab at research, though, I created a few Google alerts. Any time something came up about “Lou Grant”, it would be added to the newsreader app I use constantly on my iPhone.

I think I originally created some alerts specifically for certain writers, but I would’ve abandoned that quite quickly. One of my favourite writers on the show is April Smith and if I remember getting alerts about her new novels, I know I got more news stories that contained lines like this: “In April, Smith said…”.

Forget setting an alert for Michelle Gallery. For a brief time I knew more about the opening hours of US art auction houses than is sensible.

But if I dropped those off after the book project failed to go, I somehow left the “Lou Grant” alert in place.

Consequently, over the years since, I have been alerted to the odd thing that some of the writers are doing now, and sometimes various television executives. There’s an excellent series of interviews with Grant Tinker about the show, for instance, and I’d not have found it otherwise.

Mostly I hear about cast, though. It’s through a Google alert that I got to watch Linda Kelsey performing a drama reading somewhere. Apparently it’s through a lack of Google alert that I can’t find that again now I want to show you. Bugger.

But if I found that a couple of years ago and if the Tinker interview is further back than that, there was one thing I could regularly count on my “Lou Grant” Google alert to keep turning up.

Ed Asner.

It seemed like very other week, it cannot be more than every other month, but I would get an alert of a news story about him performing a one-man show on stage somewhere. Or going to perform somewhere. Or maybe campaigning, or doing voiceovers, or just being interviewed an awful lot about the sheer volume of work he had done and the seemingly even greater volume of work he was now doing.

So it was a more of a jolt than I would have imagined to find out this week that he’s just died.

Just died. That’s like yeah, yeah, he just had to go do that dying thing, he’ll back in a minute. And there is a bit of me that would entirely believe that.

When I think about “Lou Grant” it’s usually about the writing, which I loved so much then that it made me want to become a writer. And which I admire so much more now that I am one. But back in the day, watching this series in the late 1970s and early 1980s, it was of course the whole I was enjoying. The writing, the acting, the directing, the production, all of it.

Now I look back at it, I’ve a new appreciation for the set design. But I most definitely have a greater appreciation for the acting. It is all so naturalistic that I forgot then and I can still forget now that it is acting at all.

Tell a lie, it isn’t all so naturalistic. Ed Asner is far from that in the first episode. He’s so far from it that you feel he’s in a different series to everyone else. But then for that first edition and perhaps a few after it, he was.

Never before –– and significantly, never since –– has a half-hour sitcom spawned a one-hour drama. But that is what happened. Ed Asner played grumpy Lou Grant for seven years on “The Mary Tyler Moore Show” and then he played the more layered version of him on his own show for five.

So if Asner thinks he’s still in a comedy in episode one, you can understand it. Or you can now. Back then, I may not have consciously registered the different tone between him and the rest of the cast, but I felt it and wondered what was going on.

Oddly, “The Mary Tyler Moore Show” never really played in the UK. Even more oddly, one of its sitcom spin-offs did: “Rhoda” was a hit here. So when this “Lou Grant” show started, I hadn’t the faintest idea that this character had any history.

I sound like I’m criticising Asner for how he performed in those early episodes and I suppose I am, but really I’m appreciating what a giant and unprecedented job he was in the middle of pulling off.

There’s a lot else to admire about the acting in the show, but that’s the element that sticks out at me. I thought that this and those constant alerts about new shows was the specific reason that I was so startled by Asner’s death even at age 91.

Here’s the thing, though. I’ve been thinking about this for days and the reason I’m jolted by his death is bigger than I thought. Any time anyone you’ve even heard of dies, of course you’re sad about it. When that someone is a direct connection back to your childhood, it’s of course more, even when that person has never heard of you.

But beyond that, there’s this. There are actors I like, actors I don’t. Certainly there are performances I relish and ones where I’m glad they didn’t do that to my script. I would not have said that there is any actor who has inspired me. I would not have said Ed Asner has. This show’s writers, certainly. I’m so single-minded-focused on writing that it’s writers or maybe certain producers I know enable certain writers who I credit.

So where I would have told you that I am a writer because of “Lou Grant”, I of course meant the show rather than the character.

Except.

“The Mary Tyler Moore Show” was beyond a hit in the US. It was such a success that – cutting a story at least in half – CBS gave an on-air commitment to a spin-off for the Lou Grant character. You could dream of such a deal now, but such was the popularity of the comedy that CBS bought 13 episodes of “Lou Grant” straight off.

It was called an on-air commitment, but it was really pay or play. If CBS had aired the first couple of episodes to disastrous ratings, I’m sure they’d have pulled it and just eaten the enormous cost. Whatever their thinking was, the drama that made me a writer got on air and had 13 episodes in which to shake out things like that naturalistic versus more comedic acting.

I owe a debt, then, to the writers of “The Mary Tyler Moore Show,” a series I’ve barely seen and certainly hadn’t the slightest notion of back when I was starting to mount up this bill. Creator/writers Allan Burns and James L. Brooks became familiar names to me on screen through creating “Lou Grant”, along with Gene Reynolds. But CBS had such faith in writers that it had tried to fire Burns and Brooks when they were developing the Mary Tyler Moore series and it was only Grant Tinker’s intervention that prevented them being out on their ears.

Which means score one to Grant Tinker, but this also tells me that really CBS gave an on-air commitment to Ed Asner.

So a show that meant this much to me exists because of an actor’s performance in a series I didn’t know.

I struggle to bring myself to say that therefore I am a writer because of Ed Asner, but it isn’t half looking like that. I thought it was unusual enough to be able to pin one’s career down to a single moment like a TV show, but to pin it to a performance I hadn’t seen, that’s just eye-widening.