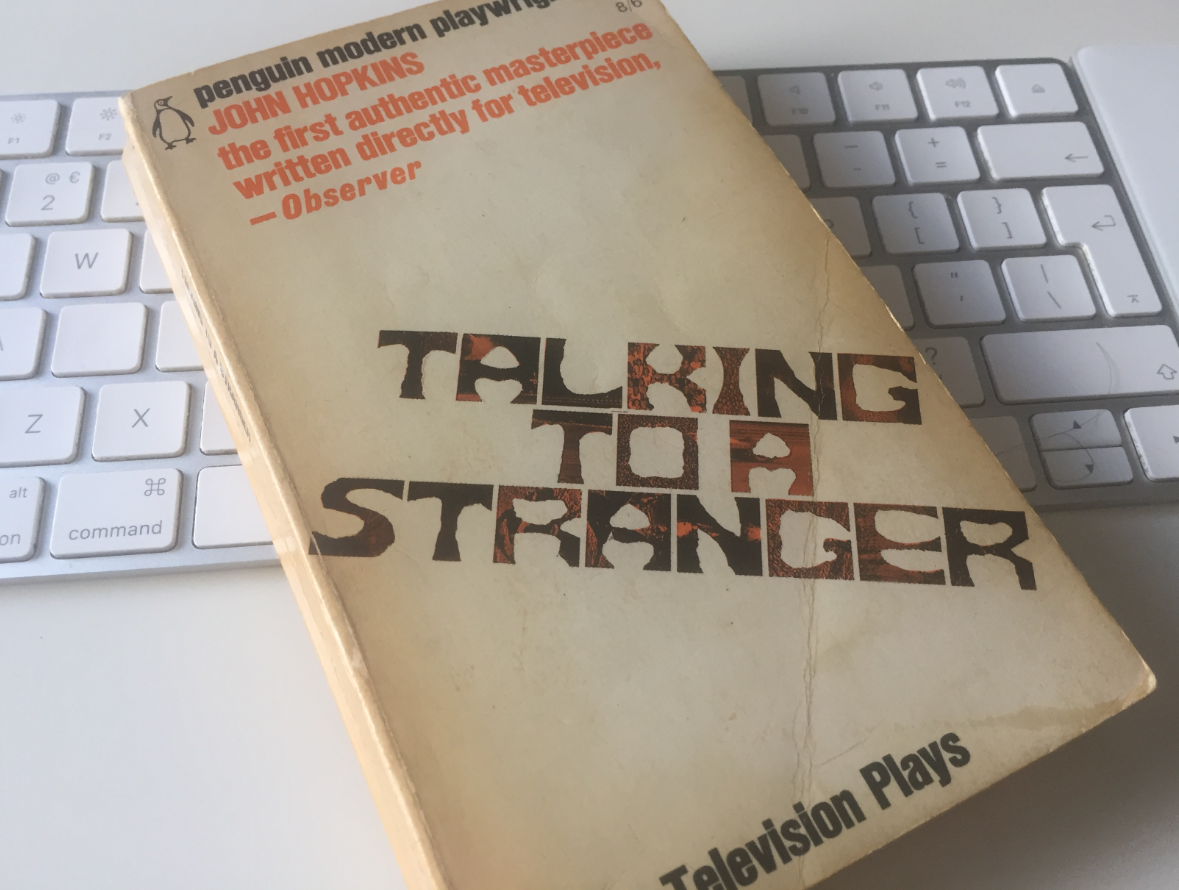

Angela says it was in the Lake District. Neither of us can remember the year. But I have a vivid, visual memory of standing in a secondhand bookshop with my hands shaking.

For there on a shelf that I could so easily have missed was Talking to a Stranger by John Hopkins. This is one of Britain’s most significant television dramas and here were the published scripts. I had no idea there was a book and for all I knew of the show, I hadn’t seen it.

It’s a series of four plays, also known as the Hopkins’ Quartet, and it’s the story of one weekend with a family. You can read or presumably watch any of the four and they are separate, they stand on their own, and they are exceptional.

But as well as my hands shaking when I found this, I also remember something else. This memory isn’t visual, it’s not as specific, it’s really more of a feeling. Yet it has the same punch to me because it was the moment in reading the fourth script that I understood.

Each play is set on this same weekend and is told from a different character’s perspective.

These days that’s known as the Rashomon format. There’s this film I’ve still never seen called Rashomon which tells the same story over and over from different views.

There are also a couple of rather joyous episodes of Leverage which do it. Most notably, there’s one written by John Rogers where all five of the regulars take turns to tell their version of the same crime. The episode is even called The Rashomon Job.

I relish that episode for its wit and chutzpah but its greatest moments are all when it shows us how each character sees the other four.

It’s funny, clever and satisfying but it is also a construct. You know the plot came first or at least it wasn’t initially about the characters, it was about the form.

Whereas this moment, this memory I have is how I felt reading the last Talking to a Stranger script and realising. Suddenly seeing why these four plays are being told this way. Seeing that the entire quartet was always building to the same thing. Realising whose story this really is. No trick, no gimmick, just the way this story had to be told.

I was telling someone about this today and found myself saying that this moment changed me.

It definitely contributed to my obsession with time in drama but I swear I was a different man after I read this.

I’ve had people change my mind – I do enjoy that – and I’ve had experiences that shaped how I see the world. But here were words on a page, words first broadcast when I was one year old, that affected who I am.

You’ll notice I said broadcast. I was going to say written but actually that’s part of why these plays are famous. For all their modern pace and the vivid characters, the production of Talking to a Stranger belongs to another time.

The four plays are different lengths, for instance. No fitting it to two hours with ad breaks. And while Hopkins famously wrote Z Cars episodes over weekends going from no idea to filmable script before Monday morning, he didn’t do that here. Instead, he was late.

I mean, really, really late.

I want to say that he delivered the scripts to the BBC a year after he was due to. That may be an exaggeration. What I’m sure of is that it was long enough that they were into the next year.

And apparently the BBC barely chased him. What I’ve heard is that they may have rung him up and asked how it’s going, old chap, but that was it.

I twitch at the idea of missing a deadline by months. I un-twitch at the notion of the scripts then being complete. No emails back and forth asking for a tenth rewrite to pass the time.

I’m also frightened to watch Talking with a Stranger.

Very many years ago, I did see the first play and it was everything it was supposed to be, it was everything the script was. Also it had a teenage Judi Dench. I don’t know why that surprises me: she must’ve been a teenager once, but there you go.

I’m telling you all this now because late one night this week, I found Talking to a Stranger on the BBC iPlayer. Some big rights issues must been settled recently because suddenly there is a huge amount of truly superb drama on there but I never imagined this would be.

I think I stared at the listing for a full minute, processing this.

I definitely decided not to watch right then. It was gone midnight, I’d done a 16-hour writing day, I want to be fully conscious to enjoy this.

And I am wondering what it will do to me. It might be easier to just go see the new Mission: Impossible film instead.