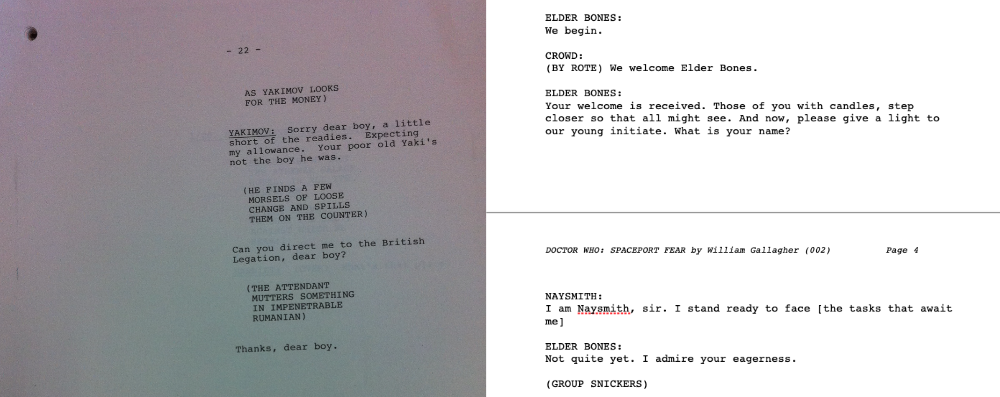

On the left there, a somewhat poorly-scanned page from Alan Plater’s screenplay of Fortunes of War, based on Olivia Manning’s novels. On the right, a page from my Doctor Who script, Spaceport Fear. I am shocked to realise that 25 years separate the two, but what joins them is who said these first words of the characters. Prince Yakimov on the left and Elder Bones on the right were both played by Ronald Pickup, who died this week.

I’m a bit numb about that. It’s not like I knew him well and considering that he’s had the most astonishingly long and varied career, it’s a bit bad that I inescapably associate him and that fantastic voice of his with these two roles.

But Fortunes of War means the world to me. I can sit here, talking to you, and play pretty much the entire serial in my head, frame by frame. If you don’t know it, I’d say I envy you having it to enjoy, except that it’s quite hard to find now. Search YouTube for Fortunes of War, Emma Thompson and Kenneth Branagh. That’ll do you.

And you can always buy Doctor Who: Spaceport Fear to listen to.

Only, if the name Ronald Pickup makes me instantly picture Prince Yakimov saying “dear boy” in that voice, when I close my eyes I’m walking into the Big Finish studio where that Doctor Who is being recorded – and I’m trying to place the voice of whoever is playing Elder Bones.

I don’t remember why I didn’t already know who all the cast were. I certainly knew that Colin Baker was the Doctor and I was excited at the prospect of seeing Bonnie Langford perform my lines as Mel. I suspect that something changed, that I hadn’t been due to go to the studio and suddenly I could. Oftentimes you don’t go because you’re off writing something else, but whatever the reason, whenever the chance, it is gorgeous to hear first-class actors delivering your lines.

So I’m walking into the control room, I’m hearing that voice, and I’m also absorbing the news that Bonnie Langford isn’t there. I didn’t meet her, I’ve still not met her, and on that day her lines were read in by another member of the cast. Read in so well that I doubted the news, I was so sure that this was Mel talking to whichever man had that great voice. (Langford couldn’t make that recording day so she came in a week later, I believe it was, and recorded all her lines in one go then. I thought that must sound awful, but listen to the story: you cannot tell she isn’t reacting to everyone around her. It’s a remarkable job by everybody from Langford herself to director Barnaby Edwards and the whole crew.)

Anyway.

I was obviously late because they were all deep into recording. And the way the studio is laid out, I could see Colin Baker very easily, but some of the others were completely out of view. So I had this glorious voice filling the control room as if coming from nowhere. I know I know it, I know I recognise it, but it was a good twenty minutes before there was a recording break and I got to see that, yes, it really was Ronald Pickup.

In that twenty minutes, I went from wondering who the voice was, to wondering whether that was really Mel talking to him, and through the stages of mentally comparing what they were all saying to what I’d written. And then so very quickly into forgetting it was all my words, all my story, and just completely believing that this was the Doctor and Mel in some serious trouble.

Big Finish always gets superb casts so I freely admit that I’ve been starstruck at regular intervals. But for half an hour or so over lunch that day, I got to natter away about Alan Plater and Fortunes of War with Prince Yakimov.

Dear boy.