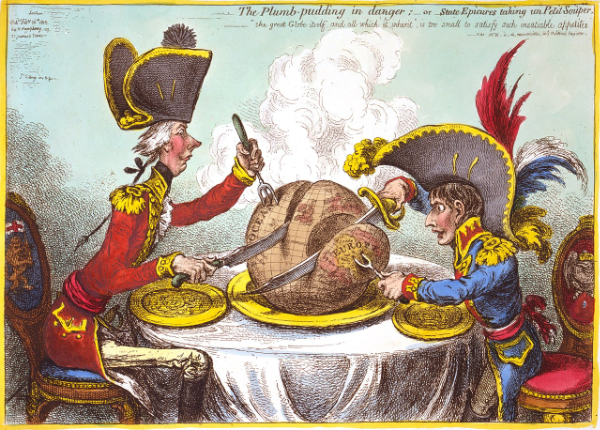

Maybe as much as thirty years ago, I came across a political cartoon called “The Plumb Pudding in Danger” and I have wanted to use that as a title ever since.

Last Monday, I did.

It’s so long since I found that image that I can’t remember what I was doing or even much about it: I have to refer to my own script in order to tell you that it shows Napoleon and William Pitt the Younger carving up the world which is depicted as a plumb pudding.

James Gillray’s The Plumb Pudding in Danger (1805)

I had that image projected onto the wall at The Door theatre in the Birmingham Rep as part of Bad Choices, a night of plays by Cucumber Writers. Even if you’re as historically ill-informed as I am, you can see that cartoon is an ancient thing and I needed there to be no doubt that the play was present-day. So I had it as if it were on the wall of the office the play is set in – and next to it I had an image of Theresa May.

Or as the script says: “Theresa May or whoever is Prime Minister when we stage this.”

I wrote all this in the script and no doubt whoever directed the play would’ve had the images shown as described, but in this case that was me. I directed it.

It was my first time directing an evening of theatre so it was first proper time as a hyphenate. A writer-director.

Only, I also then ended up producing.

And as my Plumb Pudding script has a character who you only hear over speakers, I also acted the part offstage with a microphone.

Writer-director-producer-actor.

Just go back over those words, would you? How far through do you get before it stops sounding impressive and instead starts to seem a bit cheap?

It is fascinating, though, to briefly hold all these different perspectives in your head. I was sitting in the audience for most of the evening, more aware and more conscious, more in the moment than I can easily recall. Each beat of each play, examined. Each reaction from the audience.

It makes you oddly dispassionate, or at least it did me. So for instance, I think as a producer I fell short because I took my eye off the ball about promoting the evening enough. I concentrated on the material and making it happen. As a writer, I was good but there’s one character in my piece that I need to work on. As an actor, I was adequate on a microphone but if I’d actually shared the stage with my cast, I’d have been blown away.

And as a director, I was strong on the short plays and very clear about what I wanted, very able – I believe – to have everyone contributing. But we also had two poems in the mix and there I was out of my depth. I could direct some stagecraft, I could direct about pacing and where to aim or emphasise certain parts, but otherwise it was a poem. It rhymes, I thought. And that was my extent of expertise in it.

Those poems were by Rupi Lal. The other plays that I directed were by Louise Marshall and Emma Davis. There was one more play by Matthew Warburton that he brought in pre-directed so I could just relish watching that one.

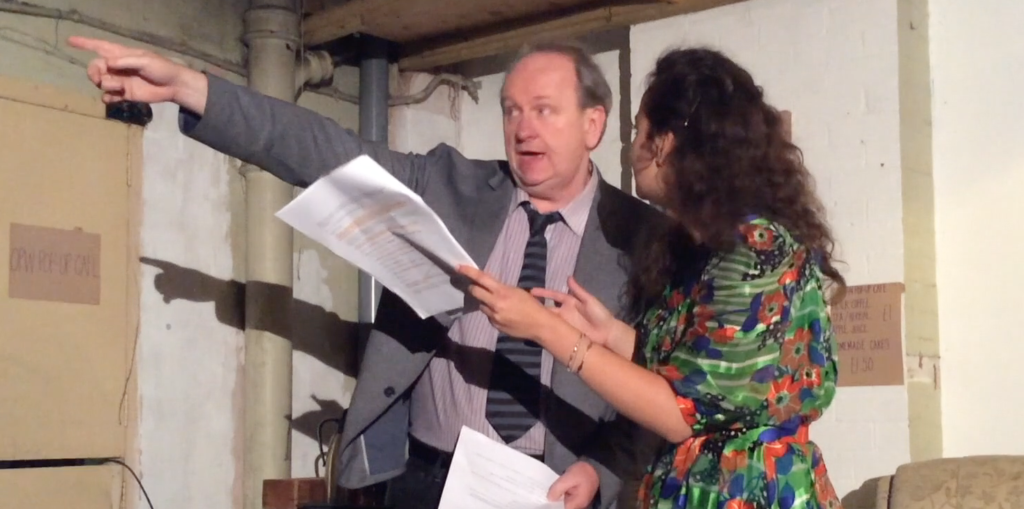

He starred in his one with Kath Waters. My cast was Alan Wales, Deb McEwan and Dru Stephenson.

My co-producer was Angela Gallagher.

And if you want an night of theatre doing, these are the people you must get. I still and will always believe that it has to be on the page, but there were a hundred moments during rehearsals when I’d stop to just marvel at what the cast were doing with the material.

There were also a hundred thousand moments beforehand where I was sick to my stomach at the entire prospect of directing. But only you know that and as far as anyone else is concerned, when can I do it again?