I read the starts of two friends’ novels this week.

Wait.

That sounds like I chucked them aside, couldn’t be bothered to finish them. So far both friends only have the starts of their novels. Normally I wouldn’t read anything until it was complete but there were special circumstances. One was being readied for an agent who has a publisher waiting to see it – and his publisher is in for a treat, I can now tell you – and the other was at a much earlier stage but I’m working with the writer generally and we’d talked about it, I wanted to see it. If she’d had the rest of the novel, I’d be reading that now and pointing you at Amazon for it.

But while we wait for both of these books to be finished, I want to figure out something that happens to be in both of them. It’s actually in every novel: it’s about the names we give characters. It was just noticeable in these two because hers had a character I am sure is named after two famous ones and I’m dying for her to reveal I’m right. And his unfortunately had a name that might be a problem.

I can’t tell you the name but, to give you an idea of the issue, it was like a more sensible version of Cormoran Strike. Cormoran is the lead character in JK Rowling’s The Cuckoo’s Calling (a rather excellent crime novel she’s written under the name of Robert Galbraith. Don’t get me started on pseudonyms. I was once paid extra by a newspaper to make up a couple of bylines so that it didn’t look like I was the sole writer on a supplement project. One of the ones I picked was Dennis Price. That’s the ‘real’ name of the photographer character in Lou Grant, the guy usually called Animal. Nobody would get that. Except Dennis Price, an uncle of my wife Angela’s. I’ve never told him the truth.)

Anyway.

This guy’s novel features a character who has a much more real-world and believable name than Cormoran Strike. You read his and accept it unthinkingly whereas with Cormoran you go through the stages The Simpsons described for The Beatles’ name.

PRINCIPLE SKINNER: We need a name that’s witty at first, but that seems less funny each time you hear it.

There are reasons why Cormoran Strike is called that and I particularly like that Rowling only suggests the reasons quite far into the book. Explaining it directly, explaining it immediately would be like defending it and that would somehow be calling out that it is an author’s contrivance instead of a real character’s – a real person’s – name. My guy doesn’t need to suggest or explain, his character name is just effective and believable. But it’s close enough to Rowling’s that I had to tell him.

It’s touch-and-go. I talked about it with him and though he sees the problem, though he’s looking at changing it, I wouldn’t be overwhelmingly surprised if he decides to stick with his first choice. You’d think that a name is a name, that one is as good as another, that a swift search-and-replace in the word processor makes it easy to change a name. But if you do think that, you also won’t be surprised that I’ve read a lot of manuscripts and scripts where the writer has searched-and-replaced but you can tell. I’ll never tell you who, but one writer obviously changed the name Bill to something else, which gave rise to this at the start of a chapter:

“Dick, please.”

I’ve had to change names for legal reasons or because, like this guy with the Rowling-ish name, I’ve spotted or been told something is too close to something else. It’s so hard to get a reader into a story that you can’t afford to throw them out again and if I had a character named James Bond, it wouldn’t go by unnoticed. But changing names is wrenching and I love that I can show you this quote from David Lodge who wrote in The Art of Fiction that:

The invention of the word processor has made it easy to change the name of a character at a late stage of composition, just by touching a few keys, but I would have a strong resistance to doing that to any but the most minor character in my fiction. One may hesitate and agonize about the choice of a name, but once made, it becomes inseparable from the character, and to question it seems to throw the whole project en abime, as the deconstructionists say.

I read Lodge’s book twenty years ago but mise en abime didn’t make it into my ideolect: if it’s new to you too, it means sent into the abyss. But while I’ve got you with the page open in Lodge’s book, take a squint at this next bit:

I was made acutely aware of this in the process of writing Nice Work.

This novel concerns the relationship between the managing director of an engineering company and a young academic who is obliged to “shadow” him… it is generally a… straightforwardly realistic novel and in naming the characters I was looking for names that would seem “natural” enough to mask their symbolic appropriateness. I named the man Vic Wilcox to suggest, beneath the ordinariness and Englishness of the name, a rather aggressive, even coarse masculinity (by association with victor, will and cock), and I soon settled on Penrose for the surname of my heroine for its contrasting connotations of literature and beauty (pen and rose). I hesitated for some time, however, about the choice of her first name, vacillating between Rachel, Rebecca and Roberta, and I remember that this held up progress on Chapter Two considerably, because I couldn’t imaginatively inhabit this character until her name was fixed.

Eventually I discovered in a dictionary of names that Robin or Robyn is sometimes used as a familiar form of Roberta. An androgynous name seemed highly appropriate to my feminist and assertive heroine, and immediately suggested a new twist to the plot: Wilcox would be expecting a male Robin to turn up at his factory.

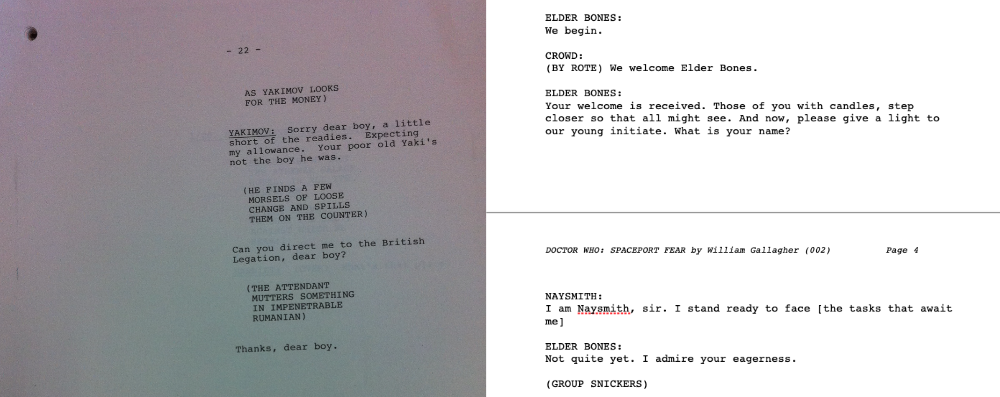

I’ve had the same concerns and the same delays but I’ve never delved so finely. I think I tend toward the more natural names and avoid connotations and allegories and deeper meanings – though listeners to my Doctor Who: Wirrn Isle didn’t like my character names Toasty and Iron, absolutely perfect though they were – but I also find it hard to change names. Even between projects. I must’ve written a good dozen scripts before I started getting anywhere, I could well believe I’d done twenty if you wanted to insist, and a very early one featured a woman called Susan Hare. I liked that name so much that in the next script, stuck for a new name, I borrowed it. And did so again a few years later. And at least once more.

I’ve had the same concerns and the same delays but I’ve never delved so finely. I think I tend toward the more natural names and avoid connotations and allegories and deeper meanings – though listeners to my Doctor Who: Wirrn Isle didn’t like my character names Toasty and Iron, absolutely perfect though they were – but I also find it hard to change names. Even between projects. I must’ve written a good dozen scripts before I started getting anywhere, I could well believe I’d done twenty if you wanted to insist, and a very early one featured a woman called Susan Hare. I liked that name so much that in the next script, stuck for a new name, I borrowed it. And did so again a few years later. And at least once more.

As it happens, poor Susan has never been in a script that got made or I’d have to stop doing this. But it tickled me one day to realise that, with some effort, you could actually link every one of these scripts and have every one of those scripts be about the same woman. Not perfectly, I’m relieved to say her character was different in each, but chronologically. The child Susan Hare could have become that teenage Susan Hare who could have just about become that adult Susan Hare. It got so I spent a ferociously long time thinking about what would make that child turn out that way. I started sketching out other scripts that might fill in the gaps. If I ever do The Susan Hare Chronicles, that’s where it started.

More often, I am vividly clear on the character but I imagine I’m not fussed about the name. I know changing it later will be a wrench, I know that I get very connected with the names, but at the point of creation, I have extremely often just looked up at the bookshelves next to me and combined a couple of different author names. Consequently I’ve had characters named Beiderbecke a bit. Also some Woodwards and Bernsteins. Just between us – please don’t tell anyone else – I am quite a bit chuffed that this looking-up-at-bookshelves now means I often risking naming characters Gallagher.

There’s never a connection between me or those other authors and the characters, I’m never trying to name someone after someone. That Wirrn Isle also featured a woman named Veronica Buchman and she was named after the fictional characters Veronica Mars and Mad About You’s Jamie Buchman. (I do love the name Veronica Mars with its mix of old-fashioned forename and unusual surname. Until a character in that TV show pointed out that Veronica Mars drives a Saturn car and lives in a town called Neptune, I hadn’t even connected Mars with the planet. “Move Uranus,” she tells that character. “Mercury’s rising.”)

I do have an Izzy somewhere, in something, I’ve gone blank now, and she was named after a BBC Radio producer just because I liked her name. I liked her too, but I really liked her name. Otherwise, I can only think of one single time I’ve named a character after someone: there is a Jyoti Cutler in my latest Doctor Who, Scavenger, and she is named after Jyoti Patel. She’s the script editor who took a chance and commissioned me to write for Crossroads. I doubt she even remembers me, but I am grateful and I liked her a lot. But I also just really liked her name or I wouldn’t have used it.

I mean, much as I like you, I’m not going to use your name in a script or a book. Your name is yours: it means you to me. I loathe these contests where the winner gets a character named after them, usually in a crime novel, usually a character who gets murdered early on. Couldn’t do it.

Because names are that important to me. You may have gathered that.

Just don’t get me started on titles.