To be fair, I’ve done it very badly. If you’ve kept up with my occasionally incessant nattering on twitter then you’ll almost certainly have seen me posing and sometimes that will have been about this. If you’ve caught up with my updates on Facebook then you’ll have seen me wobbling about it. But, until now, I’ve not said to you here that I wrote a Doctor Who audio play.

You thought it was going to be something more exciting. But it is for me and since I tell you everything, I actually don’t want to focus on that play, I want to examine why I’ve been so reluctant to talk about it. More than reluctant, I’ve positively refused to write to you about it. I will tell you right away that this boils down to how I tell you the truth here.

So you know immediately that this is me, it isn’t you. People who get Doctor Who, who have it wired into them as I and so many of us have, they’ve all been very generous. People who don’t get Doctor Who but see that I do or see why it’s such a hard show to write for, they’ve been tremendous.

Yet I’m of course fully aware of how small my Who is in comparison to the hundreds of Doctor Who stories out there. Equally, I know it’s tiny next to the, say, twenty-part BBC Radio 4 serials I stuff my ears with. My little Doctor Who is a trifle, but hopefully a nice trifle. To be clear, what I wrote was one single 25-minute audio episode of Doctor Who starring Peter Davison and Sarah Sutton from the TV show. It guest-stars Susan Kyd, who has a particularly fantastic voice, Duncan Wisbey who can and does play just about every character in the piece, and John Dorney, who took my Janson Hart character and forever, for better changed how I’d heard that character on the page.

My tale is called Doing Time and is third of four such one-parters on the release Doctor Who: The Demons of Red Lodge and Other Stories. Those other stories are by Jason Arnopp, Rick Briggs and that same John Dorney who by now is just showing off.

So I find I’m in good company and I think my piece stands comparison. It’s as good as it is because of my working with script editor Alan Barnes, director Ken Bentley and Big Finish producer David Richardson. On the recording day, Peter Davison asked some smart questions and we all improved it on the spot. I love that drama is a collaboration yet I also love that when you listen to the four plays on this release, you know it is impossible that any one of us could’ve written any of the other stories. Doctor Who is freeing and alive and open to myriad ways of telling stories – even as it’s, technically, an extraordinarily hard format to write for. Let me buy you a drink and lecture you on how Doctor Who, of all things, is not about time.

That’s a slight problem for me because, dramatically, time is my big thing. I don’t mean time travel, I mean time: it seems to me that time is a prison and the best any of us can do is bang on the pipes a bit to pass messages on. I’m interested in how we change over time, how our perceptions of events can be utterly reversed just by when we start to observe them. I am particularly drawn to how none of us can ever undo anything we’ve done. Living with what you’ve done, living with something you cannot live with.

You can see why I didn’t enjoy writing for Crossroads.

And you can see why I’m drawn to the TARDIS. In fact, for as long as I’ve been writing, I’ve fantasised about the day I could type the scene heading: INT. TARDIS.

I’m still waiting for that. With Doing Time, I couldn’t work the TARDIS into the story and instead I got a true shiver running through me the day I wrote my first line of dialogue for the Doctor. All he said in it is:

DOCTOR: August, I think you’ll find.

Doesn’t sound like a classic right off the page, but I could hear Peter Davison’s Doctor saying it in my head as I typed. And a few months later I heard him outside my head.

I remember working out when I’d had a million words published in magazines or whathaveyou; can’t remember now when that was but it was before I went freelancing in 1996. In all those words then and all these words since, I’d not had a shiver, not expected to, not heard of anyone else having them. But there it was.

Only, I still couldn’t wedge the TARDIS into the story without some almighty contortion and I so wanted to. I did it, actually, I got it in there in the first draft. I almighty contorted. But the aforementioned Alan Barnes just looked at me. Actually, he looked at me down the phone but I understood. “You’ve almighty contorted there, haven’t you?”

So, no TARDIS and anyway, Doctor Who is not about time. You can think of examples where it is, especially in Steven Moffat’s very best stories. But on the whole, the TARDIS is a vehicle to deliver the Doctor to where the trouble is and that’s it.

Yet, as I say, it’s time and not time travel that I’m interested in. Long, long before I got to pitch to Big Finish, I was thinking about what time means to the Doctor. On the one hand he’s very old so his perception is different to ours. (There’s a lovely line by Johnny Byrne in Arc of Infinity where Peter Davison’s Doctor says: “Oh, you know how it is. You put things off for a day and next thing you know it’s a hundred years later.”)

The Doctor also darts about a lot. Never stays anywhere for very long. It’s a function of the series and its need to get him on to the next story but it seems to me that this is a key part of him. I wanted to know what he would feel if he couldn’t leave, if he knew for certain that there was nothing he could do but stay somewhere.

So I put him in prison.

Locked away with the absolute knowledge that he was going to be there for a year.

I think I was originally going to be serious to the point of boredom. You may feel I do this. I think I was very intense about it all when I worked on Doctor Who Adventures magazine and found editor Moray Laing knew his Who a thousand times better than I did. I owe Moray for a great time writing for him, I owe the then-deputy editor Annie Gibson for the same thing, but Moray also led me to Big Finish. Helen Hanff has a nice line about Q, Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch, where she thanks him in a dedication saying that it is “not to repay a debt, but to acknowledge it.”

Moray introduces me to Big Finish and – at least two years later – I’m writing for them and Alan is pointing out that I’ve started my script by describing the prison doors as being like the ones in Porridge. You don’t have to be serious about being serious, we concluded. Then Jason Arnopp gave me the great title Doing Time (I’d been wedded to Folly, the name of the planet it’s set on, and later Cool Hand Doctor) and we were off.

If you write drama then this is all old hat to you but despite everything I’ve done – a little TV, lots of little theatre, many radio projects that failed at hurdles – this job taught me why drama is the hardest and the most rewarding form of writing I know.

When you do it right, you are telling a story using only what people are not saying.

I’m a dialogue fan and I’ve had rows where, much later, I’ve realised my opponent believes dialogue is speeches (“Is this a dagger I see before me and if it is, can I use it to win this argument and save all the yapping?”) where I see it as speech (“Yeah, I’m fine”).

There are plenty of speeches in Doing Time. Plenty more where I maybe too-literally explain the action in dialogue. Hard to like that. But my favourite thing in the whole story is what happens to Nyssa: while the Doctor is in prison, his companion has got a year out there alone on an alien planet. You hear many scenes with her and I’m proud of them, but the majority of her story takes place inside your head and I’m much more proud of that.

I’ve said before that I don’t believe one can be taught scriptwriting. I think you can have your eyes opened, though, and a thing that did this to me – I may have told you this before, I call it a Damascus moment – came from something Russell T Davies wrote. Before Doctor Who, I was a fan of his for Queer as Folk and its sheer verve. In the liner notes for the DVD release, he talked about the difference between writing for soap and writing drama. He’d had to learn this, he said, and realised that it boiled down to one major thought: in soaps, people say everything they’re thinking; in drama they don’t even know what they’re thinking.

Boom. Seriously. Eye-popping boom. I already knew that in drama we lie, I hadn’t thought that we were the mess we are in real life. Scripts I wrote after that day are better than the the ones before and what more could someone give you?

Possibly they could also give you how to wedge a very complicated story into 25 minutes but I accept that is an unreasonable thing to expect from a DVD liner note.

Still, writing Doing Time, I have Nyssa not quite aware how much she’s enjoying her time outside prison with a man we never meet. Then I have the Doctor not quite understanding why she seems so happy when he’s frustrated at being stuck there. I wanted Nyssa to have a life and, importantly, a job away from the Doctor. I gave her that and I also ended up giving her a flawed romance; I think now that the romance was one beat too far. When you have a woman character, it is cheap and easy to give her a romance storyline and so of course I think I was wrong to do that. If I never do it again, I might let myself off because I did also enjoy the tale and Sarah Sutton played it with the light touch I wanted.

But this comes right back to why I haven’t told you any of this before.

Hoping to never do that type of romance story again, to not do it cheaply, means that I’ve been hoping to write more Doctor Who. Of course I have.

But it’s more than that. So long as Doing Time was all I’d done, I found couldn’t actually enjoy it. I tried. I know without question how excited I would’ve been as a boy if you’d told me this is what I’d do. And Big Finish did a tremendous job. But I’m just after telling you how it felt to write what turned out to be a successful Doctor Who story and so far as I was concerned, it wasn’t and couldn’t be a success until it led to something else. Unless it led to another Doctor Who: if get another one then you really did do your first one right. Or right enough.

I do write to explore these things that obsess me and getting to do that is a privilege. It’s not luck and it’s certainly not chance, but it is a privilege. I obviously write to eat too. But my overriding goal of writing is to keep me writing: I’ve got to know what happens next, I’ve got to keep writing and keep writing better, like.

I was commissioned this morning.

I’m writing a four-part Doctor Who drama for Big Finish.

Actually, if you want to be completely accurate about it, I’m not but I should be. I’m commissioned, I have the deadline and when I learnt this earlier today I punched the air. I must’ve also shouted “Yes!” a lot louder than I thought or perhaps forgot I was at Radio Times because suddenly there were all these people looking at me.

I’ll deny this if you tell anyone else but I nipped out to a wide area by the stairs, away from everybody, and I span and span and span.

The deadline is tight enough to cut into that joyous exultant release and actually I’ve moved on to gulping about telling what’s a rather complicated story that still won’t feature any scenes in the bloody sodding TARDIS.

Fortunately, I can put that out of my mind because you and are I talking. I thought this would be when I’d gush at you, finally able to enjoy Doing Time, and yet there’s a part of me that is using you to put off writing the next bit. I’m using you. I’m a horrible man but you’re very nice and I thank you.

Listen, the deadline on this script is really tight. But that also means it’ll be over soon and I can get right back to worrying about whether I can get another one. I’ve got to stop worrying like this: you really need to give me a talking to.

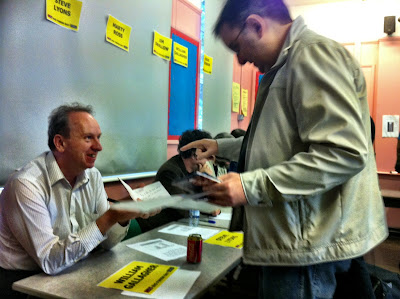

Listen, I’ve no clue how to start this but I’m burning to tell you so can you just grab a biscuit and we’ll crack on? Last Saturday I was at the Big Finish Day in Barking and I was signing autographs.

Listen, I’ve no clue how to start this but I’m burning to tell you so can you just grab a biscuit and we’ll crack on? Last Saturday I was at the Big Finish Day in Barking and I was signing autographs.