They’re called clipboard managers and suddenly I have the image of a time and motion person scribbling down notes about how slow I am. A Clipboard Manager, let’s give it initial caps and explain a bit more, is a type of software that makes your copying-and-pasting better.

It’s hard to see what you could really improve there. You copy something, you paste it. Not a lot of room for technological innovation.

Except there is.

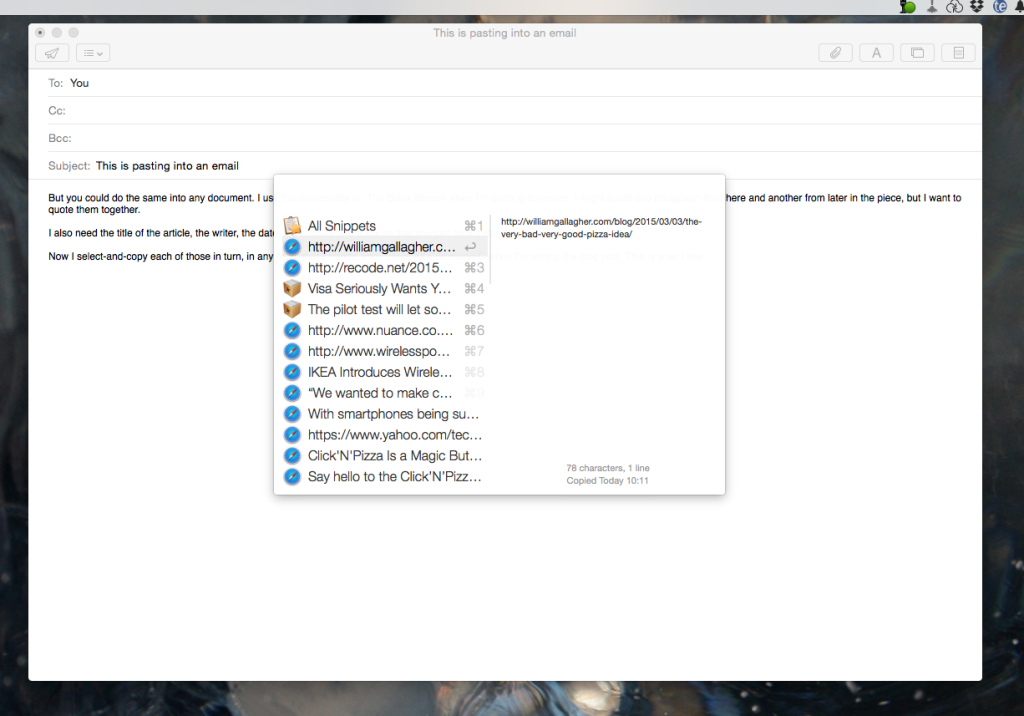

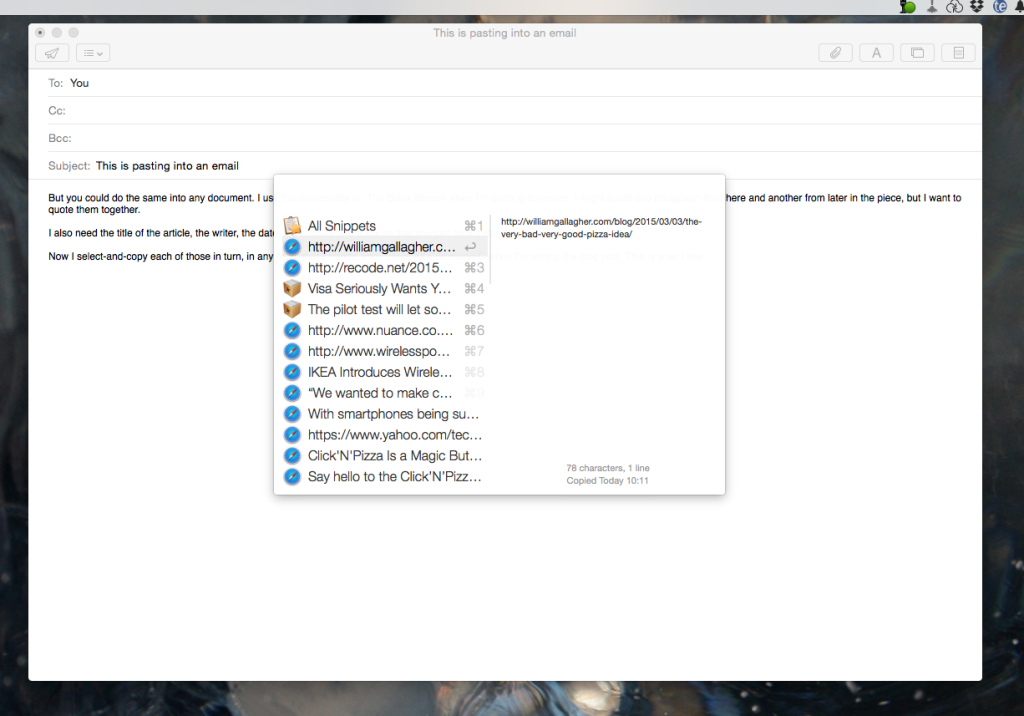

With any such app, you can copy something, then copy something else, something else. An hour later, something else. And then tomorrow paste each of those into an email. Paste them all in one big go. Paste the third thing first, the second thing second, the fourth third, anything you like.

I’ve been aware of these for a long time and paid them no attention at all. But I’ve recently reviewed two apps that happen to include this feature amongst their many others. It was the many others that made them worth reviewing but it’s this clipboard management that was most important in making me keep the software on my Mac. Here’s why. If I got to paste something, it pastes like normal. But if instead of pressing Command-C, I press a slightly different keystroke – with what I’ve got it’s Alt-Command-C – then this is what I see:

Click on that to see it full size and to also see exactly what I’ve been copying and pasting for the last few minutes. I’m hoping there’s nothing private in there.

What you see there is how the software Alfred 2 displays its clipboard manager: you get very much the same thing in LaunchBar 6, the other app I was reviewing that has this. There are others and while all of this is Mac-only, there are PC apps that do it too. Do spend some time havering over LaunchBar 6 or Alfred 2, but don’t spend any time hesitating over buying a clipboard manager. It’s that useful. I am that converted.

The Alfred 2 official website is here; LaunchBar 6’s home is there.