I’ve worked a lot in schools this week because Thursday was World Book Day. It’s a privilege to be asked into a school as a visiting author and always, always an exhausting delight. But this time, rather reasonably, I did seem to keep being asked what my favourite book is.

Depending on when I was asked, my answer ranged from Tom’s Midnight Garden by Philippa Pearce to The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath and probably all points in between. I didn’t lie to anyone, but I want to tell you the truth.

My favourite book is Misterioso by Alan Plater. It’s out of print, long out of print, and you may not think it’s the best of his immense body of work. I know you may not because he didn’t. The last time I saw Alan before he died in 2010, I mentioned this book of his and he told me that he hadn’t read it since he wrote it in 1987.

I had.

Many times.

I don’t know how many times I’ve read that book now, but it’s easily six or eight or more in those years and the last time – so far – was particularly special. I’ve got the hardback, I’ve got the paperback that followed and I’ve read them both but now I have the original typescript.

Well, no, I have a PDF of the manuscript. I photographed every page in the Hull History Centre when I was doing some research there. I photographed every page of the manuscript, all the publishers’ correspondence, two drafts of the television version that was aired and one episode of a substantially different TV script that was never filmed.

So you could say I’m quite keen on this story.

But I will tell you right now that there appears to be very little to it. In reality, well, there’s genuinely not a lot to it. When her mother is killed in a car accident, Rachel sorts out her papers and discovers that her dear old Dad is not her father. The novel starts off appearing to be a reasonably familiar tale of someone searching for their real parent.

Except in this case, she finds him and quite quickly.

It’s not about her father, it’s not about her Dad, it’s not about her mother. It’s about Rachel and how small moments become big questions and little changes of attitude become life-altering.

You can easily argue that nothing happens in the novel but by the end, Rachel’s life is transformed.

That’s it, just a little complete life transformation.

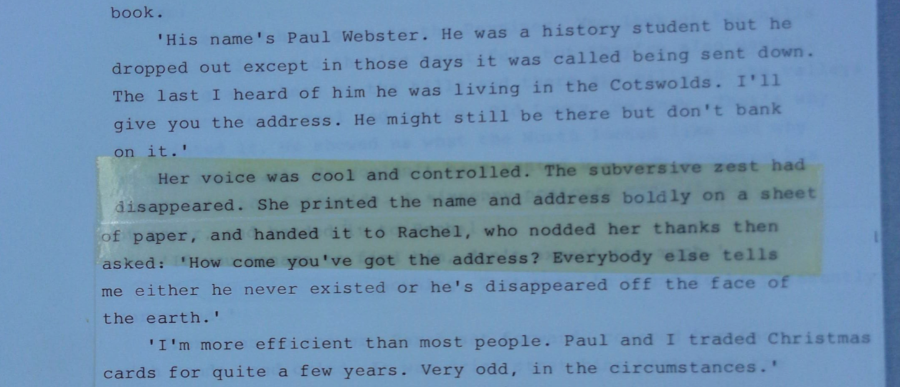

For World Book Day, though, I would like to get really specific and tell you that my favourite book is this manuscript version of Misterioso. Because as well as feeling like a special thing, having the typewritten pages my friend wrote, the manuscript also answered a question that had been annoying me since 1987.

There’s a mistake in the novel.

It’s always been there and Alan knew it was there because he fixed it for the subsequent TV version. But as ever with his work, it’s a small thing that’s simultaneously huge. In the novel, Rachel’s real father, Paul, does not know her name when they meet. And that’s despite our having learned that a mutual friend of his and Rachel’s mother used to keep him informed about how Rachel was.

It’s a slap to the reader. It’s a head-jolt and I’ve never understood it.

Until I read the manuscript.

There aren’t many alterations from the original pages but there are the odd few points where Alan rewrote and retyped something, then taped it over the first draft. Literally taped. This was 1987, this was a typewriter.

Typewritten!

And one of those alterations concerns a plot point. Alan seems to have felt that he needed to be clearer about how a character got a certain piece of information that ultimately leads Rachel to her real father. I don’t think he needed to do it, but fixing that small point early on in the book left us with this slap about a third of the way in or so.

To stand up why a character has Paul’s address, Alan creates a little two-paragraph story about how he and she had stayed in touch. He gives a reason, he makes it sensible that she would have his address. But that story, that excuse, is what then makes it impossible that Paul wouldn’t know Rachel’s name.

Alan missed it.

I read that page and the original version in the Hull History Centre and I jumped up in my seat, looking for someone to tell. Where were you?

My friend Shirley Rubinstein died this week. I keep staring at that sentence, pressing on the words, seeing if there’s any give in them, but there isn’t. Still, if her death is the jolt and the reason to want to talk to you about her, the friendship part also jolts me and also makes me want to talk.

My friend Shirley Rubinstein died this week. I keep staring at that sentence, pressing on the words, seeing if there’s any give in them, but there isn’t. Still, if her death is the jolt and the reason to want to talk to you about her, the friendship part also jolts me and also makes me want to talk. Shush, we’re in archive. It’s the

Shush, we’re in archive. It’s the