Last night I was laughing at the script to an episode of The Detectorists. Really shaking, weeping, guffawing. This kind of couch behaviour gets noticed when someone else is trying to watch The Doctor Blake Mysteries. But then it leads to information in the many ad breaks on the Alibi channel.

Toby Jones co-stars in The Detectorists and my wife Angela Gallagher, who has the most amazing knowledge of casts, told me that he’s just become patron of Claybody Theatre, the tremendous company founded by Deborah McAndrew and Conrad Nelson.

So far this is all current, topical, present-day stuff but then she tells me that Toby Jones is the son of Freddie Jones and I am instantly right back to the mid-1970s when I was a child watching him in The Ghosts of Motley Hall by Richard Carpenter.

You’ve had this, you’ve been thrown back to something and doubtlessly someone watching Motley Hall at the time was drawn to remember seeing Freddie Jones in 1967’s Far from the Madding Crowd.

Only, that 1970s viewer being reminded of a 1960s film could do nothing more than be reminded of it. Whereas no sooner than Doctor Blake had saved the day than we were actually watching the first episode of The Ghosts of Motley Hall.

It’s far from true that any film or show you can think of is available for you to watch immediately, but it feels as if it is. Last week I bought the first seasons of St Elsewhere and Hill Street Blues. Earlier this week, a friend was looking for recommendations for something to watch before her Amazon Prime trial ran out and I spent an hour trying to find the name of something I’d relished on it.

An hour.

It took forty seconds to go from Doctor Blake to a 1976 episode of Motley Hall but an hour to get a film –– solely because I couldn’t remember its name. Even when I did find it and I did recommend it to my friend, I knew I’d forget the title again so I just bought it on iTunes.

That was Your Sister’s Sister by writer/director Lynn Shelton and it is more than worth the hour I spent looking. Not only because I relish that film and have just watched it again, but also because my prodding searches online for what detail I could recall of this film also turned up a movie called My Girlfriend’s Boyfriend. Now, I know that movie under another title, Boyfriends and Girlfriends, and it’s one I delight in that’s written and directed by Eric Rohmer.

We are at the stage where a stray recollection is instantly satisfied. Where a small whim is filled in a thrice. And where to find something to watch, you no longer use Radio Times, you use Google.

It makes my mind split in two different directions. One is to think that who has time for broadcast telly any more? Television is like a delivery mechanism now, it’s a way of getting Fleabag ready for us. Television and film have become the libraries we dip into instead of the live, shared experience it was.

I can’t help but lament how everyone, simply everyone, watched when André Previn was on The Morecambe and Wise Show. Yet I can’t help but adore the fact that everyone, simply everyone, can watch that segment right now.

Well, that link is to a site called Dailymotion which currently thinks that after watching a 1971 Morecambe and Wise sketch I will want to see Miley Cyrus topless. The internet, eh?

And, well, there isn’t half an issue about the rights to this and all these creators not being paid while sites are getting ad revenue from showing them. That’s enormous. I bought My Sister’s Sister, Boyfriends and Girlfriends, Hill Street Blues and St Elsewhere but if Motley Hall is available to buy, I don’t know because I just saw it on YouTube.

The other direction my mind goes in, though, is this. Motley Hall was 43 years ago. When Peter Tork died recently, I watched the first episode of The Monkees and that was 53 years ago.

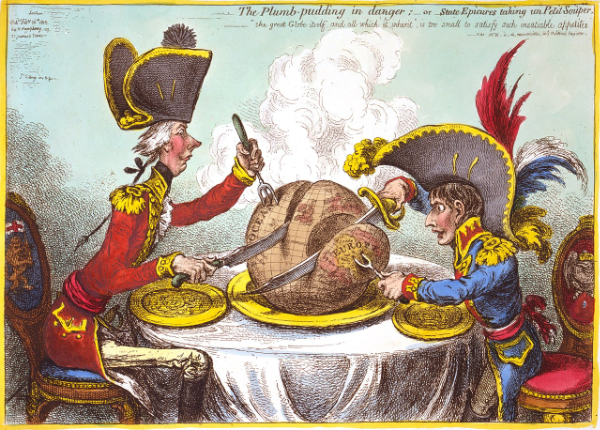

Imagine being back then in 1966 and able to watch anything you liked from 1913. Or living in 1913 and being able to watch something from 1860.

We have an unprecedented, unimaginable, incomprehensible ability to instantly taste our own culture as it was during the last half a century. Well, okay, we’re all chiefly locked to our own nation’s culture: it presumably is possible to do the same and watch any film from, say, India’s last five decades but I don’t know how to do it and those movies would be a sea to me without any markers or references or memories.

And of course this ability is locked to films and television, occasionally some radio. It only shows you what was being shown, it doesn’t really take you back in time. Except that of course it does: The Ghosts of Motley Hall has an innocence I can miss and a slow pace we lack today too.

Equally, On the Buses is about to be released on DVD for its fiftieth anniversary. The only thing more certain that this show captured its time is that I ain’t going to watch it.

We all make things for now, I don’t think anyone makes drama or comedy with much of an eye to the future beyond possible sales to different broadcasters and platforms. Yet this is mass of visual work is making me conscious both of how anything I make must be unconsciously imbued with the time that I make it –– and of how we must surely run out of room some day.

Maybe we’ll have to move to Mars just because there’s no more space to store all the episodes of NCIS.

Or videos of Miley Cyrus.