I’m not sure what 2021 was, other than not the year we expected after 2020. So I’m thinking of preparing myself for 2022 by only expecting it to be the 25th anniversary of the film “Grosse Pointe Blank” by Tom Jankiewicz, D. V. DeVincentis, Steve Pink and John Cusack.

Which makes it a quarter of a century that I’ve remembered and wished I’d written the film’s strapline: “Even a hitman deserves a second shot.”

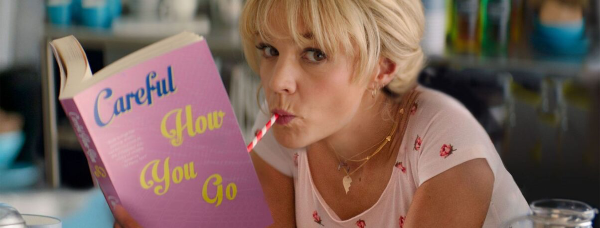

And that I’ve also remembered this scene when Martin Blank (John Cusack) meets Debi Newberry (Minnie Driver) a decade after standing her up at their school’s prom night and vanishing.

DEBI: You tell me about yourself.

MARTIN: In California, travel around a lot on business.

DEBI: That’s it?

MARTIN: Yeah.

DEBI: That’s ten years?

MARTIN: Yeah.

DEBI: I would hope for a great abduction story or something.

MARTIN: I’ve had a few thrilling moments here and there.

It turns out I’ve had what I’d call a few thrilling moments in the last year and in the last ten years, too. Back in 2012, quite a lot happened to me. Radio Times chucked me out, for one thing, and BBC Ceefax closed down forever. I still think that was an overreaction. But, God, earlier this year we had some builders in and they accidentally took away my BBC Ceefax mug. The stun to my stomach when I realised was matched only by the relief when they brought it back the next day. A mug. I’m talking about a mug. I think you’re looking at one, too.

Anyway. Ten years on, sitting here writing to you, I realise I can’t entirely remember what happened with me and BBC News Online. That was always wrapped up around Ceefax and I’d long before lost regular work with that, so I think it just dribbled away.

Still, BBC News Online continues uninterrupted to this day and so does Radio Times. I can’t imagine how they’re managing without me. They must be being very brave. And BBC Breakfast could’ve interviewed many of them about Ceefax in 2012, but they interviewed me.

Those different teams –– RT, Ceefax, News Online – remain some of the best people I’ve worked with but the pleasure of that, the enjoyment of creative people at their peak, it was pretty much replaced for me in 2012 by Writing West Midlands. I can picture the first coffee meeting with that organisation’s Jonathan Davidson, and at this distance I can even feel my nerves as he wondered aloud about whether I’d be good at going into schools as a visiting author.

I officially became a full and proper author in 2012, too, as my first book came out. “BFI TV Classics: The Beiderbecke Affair” (Amazon UK, Amazon US). It was important to me for a hundred reasons, it turns out that it was important to quite a few readers over the years too, and some day I hope to make back the advance.

It must’ve been such a strange year for me. Losing my biggest clients, effectively losing all of the work that had seen me living on the motorway between home and London. And at the same time sitting here, actually right where I am now, when the author’s copies of my book arrived. Sitting here holding that book in my hand and realising that no one could ever take it away from me. Good or bad, right or wrong, no one can un-publish that book. I’d done something I longed for and it was real.

Curiously enough, ten years on in 2022, I’m going to do something else I’ve longed for. I’ll have a play on BBC Radio 4 at last.

But that’s enough now, you’ve indulged my nostalgia far too much, you are far too kind. I recommend that you take my best wishes for your 2022 and go be you. I don’t recommend that you read on.

Because if I can’t really describe the last ten years beyond a few thrilling moments, I can detail 2021 and I’m afraid it looks very much like I’m going to. For whatever reason that deep therapy might uncover, I do tend to count things as I go and I also now appear to need to show you how many jobs I’ve done, how many scripts I’ve written, that kind of thing. I can’t pretend that it is in any sensible way useful to me so, frankly, there’s no chance it’ll be of use to you.

Yet I keep doing it and in dark moments, there’s something about the routine of logging this stuff, there’s something about how I can feel stuck and failed but, look, at least I did this, this and that number of those. It seems even more flimsy as I tell you about it, but we both know I’ll continue, so let me get this off my chest and, for once, hope you’re looking the other way.

In 2021, I did 1,853 jobs. I need to explain what constitutes a job. If you commission me for an article, that article gets listed in my Job Book. If that article requires me to interview someone, as happened a lot this year, then the interview is a job too. So it’s a lot less than, say, submitting 1,853 CVs to companies, but it’s also more than, say, just a task in my To Do app.

And I know that because my To Do app is the superb OmniFocus – which, incidentally, I apparently began using ten years and maybe six months ago –– and OmniFocus tells me I completed 7,722 To Do tasks in 2021.

Those jobs and tasks include writing Self Distract to you, of which this is the 52nd of the year and, counting on my fingers, totals something around 39,000 words. It also includes 31 workshops, 1 school visit, 12 Writers’ Guild regional newsletters, 7 appearances on BBC Radio, 242 newswriting shifts, and apparently 14 podcast appearances. That seems a bit low to me, enough so that I wish I counted better.

I doubt I’ll do it, I am reaching my level of anoraksia, but looking at the figures today, I also wonder about making more of a distinction between different types of job. Because I am close to having to guess this next: I appear to have written 1,221 articles for 4 companies in 2021.

I definitely chaired 3 panels, worked as a judge on 2 awards ceremonies, and read 523 scripts. I’m relieved to say that I wrote a few scripts too. Throughout 2021 I had various meetings that meant at least twiddling with an existing drama script, at most doing a small redraft. But I also wrote 5 drama scripts from scratch, which is possibly not overwhelming, but makes me feel okay.

Then there were non-fiction scripts. I write almost every edition of my 58keys YouTube series, of which I produced 60 in 2021 (a few aren’t going out until early 2022), plus this year I made videos for other companies, too. I think I made 6, of which 2 were scripted. Call it 66 videos produced, and 60 non-fiction scripts written.

There’s also a book, “The Blank Screen: Interviewing for Authors and Writers” (Amazon UK, Amazon US). That originated with about five hours of script I wrote in 2020 for a Udemy online course, but I’m still going to count it as 2021 since a book is a bit different and I appear to be more than a bit needy.

Maybe the thing I think I did best, certainly the thing I’m proudest of, is that I created a six-week-long Tuesday Night Writing Club and then later a six-week-long Wednesday Night Writing Club. That’s a total of 12 weeks and I adore that it is a total which is vanishingly small compared to the fact that both clubs have continued without me. Just before Christmas I was invited to join a meeting of the old Tuesday Night gang, and it is inexpressibly wonderful to see a group that were strangers before me are now deep friends after me.

On the less fantastic side, 2021 is also when term limits meant I had to step down as deputy chair of the Writers’ Guild. And workload limits meant I had to step down as chair of Cucumber Playwrights. And funding cuts meant the closure of the workshops from the Federation of Entertainment Unions.

But if you’ve read this far, let me finally shut up by admitting that in the entire year, I wrote just one short piece of fiction.

I would hope for a great abduction story, but no.