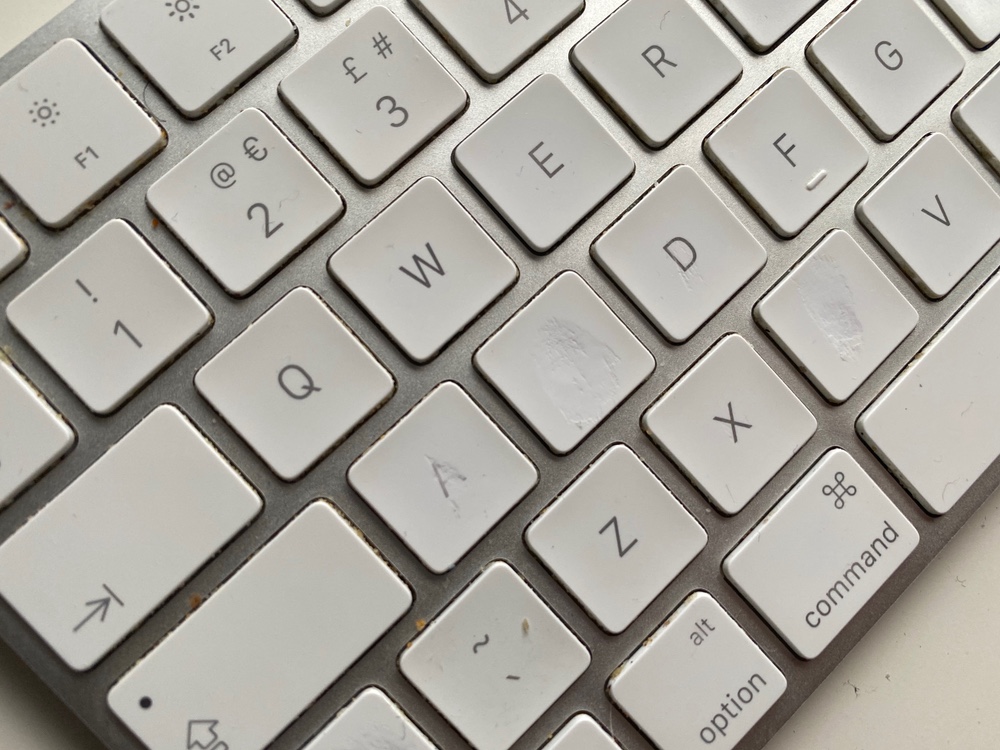

I want to write a eulogy to a dying keyboard. It’s a keyboard that has lasted me, at a conservative estimate, about three million words. Only, it is now fallen. No more English, Irish or Scottish words will go into this space bar. And certainly not any with the letter O, unless accompanied by rigorous prfreading.

Last night I mentioned to someone that I was getting a new keyboard. “You do like your gadgets,” she said. I tried pointing out what I do for a living, but it didn’t make a difference. I wanted to explain that it’s more than that I’m a writer and a keyboard is about as crucial as a an ability to lie is to a politician. But she was gone before I could finish spluttering. You get it, though, so I’d like to talk to you about this bond between us and the right keyboard.

I could wait until its replacement arrives, but it seems wrong to write a eulogy on the poor thing’s bright and shiny successor. So let me stumble on, let me occasionally try cleaning it again, let me press on in every sense.

And I ask you to please join me in saluting – wait for the silly name, none of us are responsible for what our parents call us –– the Apple Magic Keyboard 2. Magic. Grief. I suppose no one would buy the Apple So-So, Ordinary, Does The Job Keyboard 2. But Magic does seem to be pushing it.

Except it is a remarkable keyboard and I am going to miss it. Even though I’m replacing it with the Apple Magic Keyboard with Numeric Keypad. Somehow replacing it with exactly the same thing again felt like not replacing it at all. So I’ve gone for exactly the same thing again, but extended. It may make a difference, it may not, and I think now we’re heading into the fine distinctions between HB and 2B pencils.

I think I was in class 2B at school.

Look, I’m floundering around here. I want to mark the passing of a thing that I have touched pretty much daily for 1,704 days. I want to mark that therefore it has touched me too.

It’s just a keyboard. You and I could go in deep and debate the fall of mechanical keys versus the rise of chiclet-style ones like this keyboard has. There is actually something to be said about the differences between this one and the extended keyboard with numeric keypad that I’m getting. And there’s even – I am perfectly serious here, I just don’t look as if I am – a way to discuss cultural difference as expressed in keyboards.

Americans, you see, go for wide and shallow Return keys while the British prefer a long and narrow one that’s more reminiscent of history and the old Carriage Return levers on typewriters. Tell me that doesn’t say something about national identity.

And that’s just one key. This poor beloved keyboard of mine comes with another 77.

Maybe it’s the word keys. If I did a YouTube series called 58buttons, I don’t think it would mean as much to me. If this keyboard came with 78 elevated platforms upon which a legend is printed, I don’t think I’d print the legend.

But keys, now that implies unlocking what is locked. I think through typing. I could forget that a keyboard is there because of the way it’s the mess in my head appearing as the more coherent words on the screen, if only slightly more coherent. I don’t think about my fingers as I type so I don’t have to think about the keyboard. I do, though, because I enjoy those thousands and millions of key presses. I like the feel and the sound of them. Touch typing feels to me like kneading bread and I adore it.

I do also like that I’m quite a fast typist. I used to be very fast and I daren’t take a test again now to see how I’ve slowed down, but I believe I type quickly and I believe I type well and it’s good to hang on to something unchangeably positive.

This keyboard has been a conduit for everything I’ve thought from about November 22, 2015, to today. That means it embodies every problem, every bad day, every foul hour, but also every brief moment when I think I’ve written something good. There is no feeling like that and it is so powerful that it outweighs everything else.

I can’t throw this keyboard away. I can’t. I don’t know how one goes about recycling keyboards, but I’m not going to find out. I’m definitely keeping it in my office. Whisper it: I’m tempted to frame this keyboard.

Oh, look, the new one has arrived. Let’s see if it lasts the next three million words. This time I’ll keep the receipt.