For sixteen months, I’ve been working as hard as I know to be completely invisible in a project but now it’s done, I want to shout that I did it. I’ve realised that I don’t often talk to you about specific things I’m working on but this was one that I have itched to and now that it’s been officially launched, I can.

It’s the National Trust’s What is Home exhibition at Croome.

Croome in Worcestershire is a Georgian stately home and the Trust is preserving it, but the National Trust always also wants to preserve the memories of the people who lived and worked in a place. It isn’t about buildings, it’s about the people who have called these places home. And Croome has been a different type of home to many different types of people from its original days with the rich and on through its time as a boys’ school.

The thinking about this led the National Trust to explore the whole idea of What is Home? It is all about Croome, but the idea is that it is really all about us. We create our homes and then, I think, our homes rather create us back.

And as I’ve written in the notes for the What is Home exhibition, if you want to know what home really means, ask someone who’s had theirs taken away from them.

The National Trust commissioned artist Kashif Nadim Chaudry to work with the ex-pupils from when Croome was a school and also with school-age children who are currently in foster care. He ran workshops with groups and together with the National Trust team, he worked individually with the ex-pupils. It wasn’t easy, it wasn’t comfortable, it wasn’t cosy – but I was there and I can tell you it was also fun.

He asked each person to loan us an object or two that signifies home to them. Anything. Rachel Sharpe, who created the project, told every participant that their object would be treated the same way that the National Trust treats million-pound oil paintings. I was there for that too and she wasn’t kidding. There was painstaking cataloguing and there is precision tracking of every single object as it came in from the participants and ultimately ended up in Nadim’s art installation.

Nadim has done this utterly gorgeous artwork that shows all the items together. It’s plain in the sense that it’s not adorned or over dramatised, but it’s also beautiful. The objects are on plinths that gently rise and fall as you’re looking at them. It’s as if the art installation itself knows which part you’re focusing on and it offers you a better look. Then the whole piece, all of the artwork, is housed in a lattice-work frame that seems to float in the room. Just beautiful.

Photo: Jack Nelson

And so far you’ve only gathered that I wrote some notes. There’s a second room which contains a couple of panels explaining the project and the history of Croome. I wrote those and you’ll see my byline on them.

You won’t see my name on the more important writing.

And if you were anyone else, I would even deny that I did the writing at all.

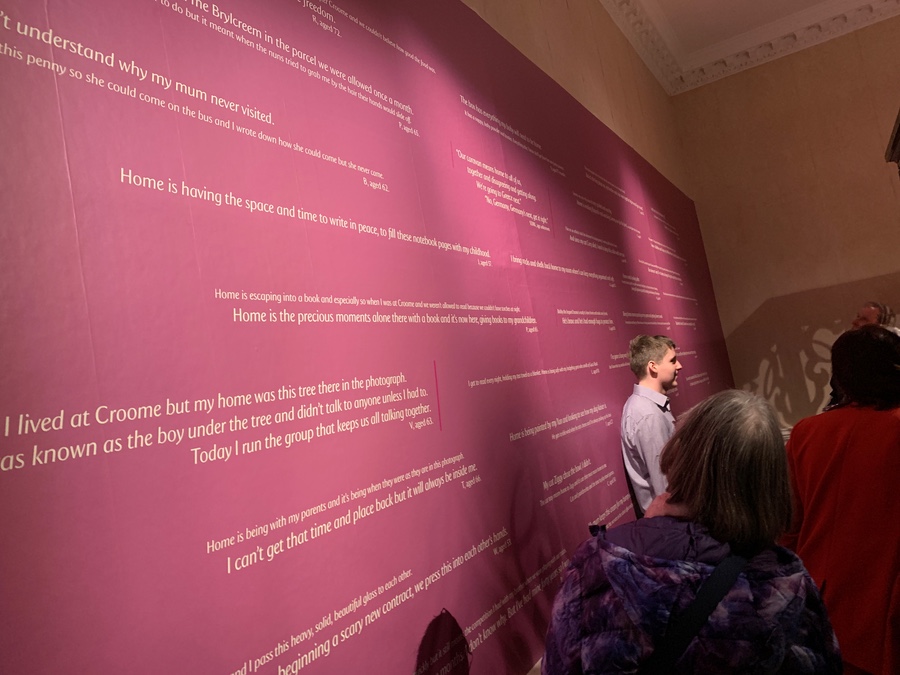

For behind Nadim’s artwork, there is a wall full of quotes from the participants. They’re all very short, never more than two or three sentences, and they are as plainly written as they are plainly displayed. I mean, the typography is exquisite but it’s presented entirely for clarity, it’s meant to be read, it isn’t trying to be pretty.

I wrote it all.

I worked with the participants, I worked with National Trust people who know the ex-pupils very well, I worked to capture what home meant to the participants. Some of the sentences are simple, direct quotes. But all of the time it was a question of conveying feeling as much as anything, of connecting you to that person. My aim was that you read this wall and you do not ever think that it was written at all, you just take in the words and it is as if those people were standing there in front of you.

I’ve told the National Trust this next bit. I said to them that if we’d known at the start exactly how many words I’d be writing, I’d have told them I’d need about an hour to write it. Compared to books and articles and scripts, it is a tiny amount of writing. And yet it has occupied me for sixteen months and I ain’t kidding when I say it’s occupied me. I have lain awake at nights thinking about it.

This What Is Home idea cuts so very deep that it was exposing some remarkably personal thoughts and feelings. I was being trusted to communicate that from these participants to you and, God in heaven, the responsibility. Also, frankly, the work was beyond me. It required fewer words than I have ever written for anything else, but it necessitated reaching deeper into myself than I ever have before.

And I have not told the National Trust this next bit.

I didn’t think I’d succeeded.

Because the text goes along with the objects that the participants loaned, and because those objects are being tracked in a database, I had to deliver my writing in an Excel spreadsheet. I’d read the latest draft of it and I’d know that I’d technically accomplished certain things, but the stories of these participants have often upset me and text in that spreadsheet didn’t.

I don’t want to knock Excel, but clearly it’s rubbish.

Because last Saturday, I read all the text again on the wall and it made me cry.

I think I’ve managed to be invisible. You do stand there and know that you have the participants and you have Nadim’s artwork. You don’t stand there and think this wall is written or composed or studied or drafted or contrived. It is plain and it is plainly the participants talking to you.

Do go have a look yourself if you possibly can. And whether you can or not, do have a read of that official website as it includes photographs of Nadim’s work plus interviews with both he and I.

Oh! Wait, one more thing. This tickles me and at the same time I think it fits everything I wanted to do. I said that there’s a second room away from Nadim’s artwork. Amongst items from Croome’s days as a school, there is also a video about the project. Last Saturday afternoon, I was standing behind a group of visitors as we watched it. And not one of them twigged that the fella on the screen talking about the writing was also the guy standing there with them and wiping his eyes.