The Blank Screen (UK edition, US edition) is all about keeping us writers creative but making us more productive. But if there is one thing we put off more than writing, it is invoicing.

Nobody tells you how to do this and we hate doing it.

So here’s how to write an invoice and if you take a squint down and think this is a long job, know this one thing:

1. It just took me 8 minutes to write my first invoice for a new company

2. It then took me 2’42” to write one for an existing client

I’ll tell you now, these were very small invoices but the amount doesn’t affect the time it takes. What you should take away from this is that for a pixel over 10 minutes work, I’d written and sent – notice that, also sent – invoices to the value of £120.00. I won’t pretend that either writing job took very long but without that 10 minutes invoicing at the end, I wouldn’t be being paid.

So it is a chore, yes, but it’s incredibly quick to do and without it you don’t get to eat.

This is when you do what:

1) When you get the commission

Know how much the fee is. If you don’t know, ask before you do the work. Your editor deals with this every day: when I’ve been a commissioning editor, I’ve known my freelancers’ fees better than my own.

Ask how the company needs to be invoiced: actually, just ask exactly this: “Do you need purchase order numbers?”

If they do, they’ll tell you the number and they’ll also tell you anything else. That new client had also assigned me a vendor number. You don’t care, I don’t care, if they give you purchase order numbers, vendor numbers, anything else numbers, you just keep a note of them and copy them out onto the invoice.

Ask specifically how you are to deliver the invoice: “Do you need invoices posted or can I email them – and what’s the best address?” Cross your fingers that they’ll say email is fine because it’s so much faster and more convenient for you.

Some firms will send you a tonne of forms to fill out with your bank details. Schlep through the lot and get it done.

2) When you’ve done the work and delivered it

Invoice. Don’t wait. The invoice has nothing to do with whether the editor will ask you to do some more work on it. Send the writing, send the invoice.

It does not help you sitting on a pile of invoices – and it doesn’t help them, either. A magazine issue will have a budget allotted to it and ready to spend. In theory you should always be paid whenever you get around to invoicing but in practice, good luck getting cash if you let it slide past the end of the financial year. Or perhaps, good luck getting commissioned by the firm again if you do.

So invoice promptly.

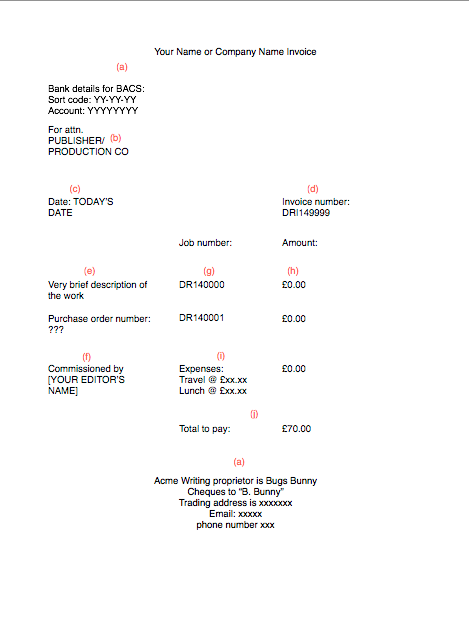

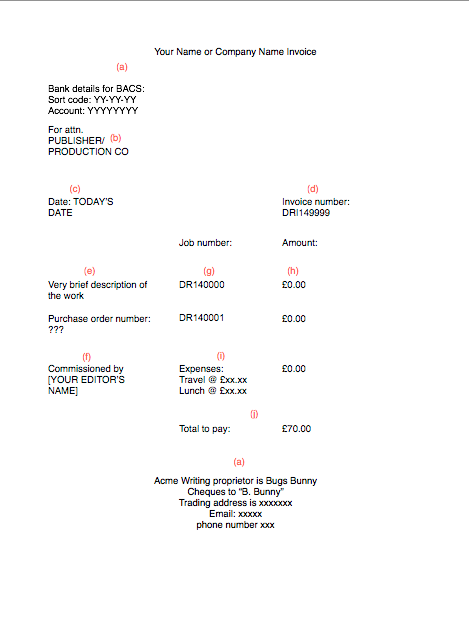

(For a larger version, download the annotated example invoice PDF.)

And this is how you write that prompt invoice:

a) Your name or company name at the top

You could include a company logo if you like, but don’t try to make this pretty, work to make sure that it is clear.

Definitely include your bank BACS details so that they can pay in directly. You want this. You really want this because it’s a right pain getting cheques, losing time going to pay them in and then waiting for them to clear. Encourage companies to pay by bank transfer and do so by giving them your business account’s sort code and account number.

You do also have to give them the ability to send cheques. That means listing your postal address and stating specifically how cheques should be addressed. That’ll be your name, your company name or a combination of the two: “Bugs Bunny trading as Acme Writing”.

Many people argue that you should write a line like “Payment in 30 days” and as long as some of those many people work in accounts departments, you might as well listen to them. Strictly speaking the presumption is that payment is due within 30 days so I’ve never bothered to say it but it does give you something point at when you phone up on the 31st day.

b) “For attn. Accounts Department” and their address next

c) Today’s date. This is the date of the invoice, not the work

d) Number the invoice. It’ll help if you have a system so you just know that number 12 is next

e) Describe the work

Some clients will give you the text they need for this. They’ll call it the brief or they will specifically tell you to say this or that for the invoice. It will be very short. If you’re invoicing for several things at once, the description can include an explanation of the fee: “3 days writing workshops @ £450/day”. This is where you list any purchase order numbers, vendor numbers or the like. If the client gives you any of these, use them. If they don’t, shrug.

State the date of the work here. If you’re doing an event, say, then the date is the date of that event. For a written project, it’s the date you were commissioned. That’s sometimes hard to pin down, especially when you’re doing all this months later. Find an email and use the date of that.

State any date or other detail given you for when the work will be published. If it isn’t a specific date, then it’ll be something like “Acme Magazine October Issue” or “BBC week number 12”.

f) Who commissioned you

If there’s a problem, this is who the accounts department will go to first. Usually your editor’s name.

g) Number the job

This will certainly help when you’re invoicing for several things at once – “3 x 2-page tutorials” – because you or the client can then query a specific job if necessary. But just do it anyway. Do it always. Number every job as you get it.

It helps you when you’re doing the invoices because you can see and then state each job quickly. It also means you don’t miss one out by mistake and never get paid for it. But it also helps you psychologically as the number of jobs keeps on going up.

It’s up to you whether you write a separate invoice for each job but only do that if you know it will affect when you get paid. Maybe three jobs are for the March issue of a magazine but one is a Christmas special. If the company states that it will pay 45 days after publication, invoice the Christmas one separately or you could end up waiting until next February to get your money.

h) Money

Next to each separate job number, write down the fee.

i) Expenses

If you have expenses and it’s agreed that the client will pay, write those down too. If you are VAT registered then make sure your VAT number is listed somewhere on the invoice and specify how much money that VAT is.

j) Total.

That’s the complete total for everything including the fee, the expenses and the VAT if you have that.

k) Save as PDF and email to the accounts department

Once you’ve done this once, keep a copy of that first invoice and use it as a template.

One more thing

This is a chore and you are a writer, you do prefer writing. But you also like technology so use it. I have one monthly gig in Burton upon Trent and when I leave there, my iPhone knows I’ve gone and OmniFocus pops up a reminder to do the invoice. I might not do it then, but sometimes I have done it on the train on my way home.

I don’t actually do that gig for the money, I’d pay them to let me do it, but that doesn’t change that it is paid, I do need to invoice, so I should invoice promptly.