Take a look at this, please.

I’m trying to see from your face whether you recognise any of that, but all I can see is that you’re looking a lot younger than me. I will try to still like you.

I’m trying to see from your face whether you recognise any of that, but all I can see is that you’re looking a lot younger than me. I will try to still like you.

Anyway, if you do recognise it, I guarantee that you only recognise the first 17 words of the speech, not a single syllable after them. And you’re not really reading those 17, you’re hearing Debbie Allen saying them.

It’s the Fame speech. I think Allen delivers those lines in the opening title sequence of every one of that show’s 136 episodes. Certainly it’s in most of them, and I’ve just recently learned that she does different versions of it for some of the different seasons of the series.

Debbie Allen is this remarkable talent, a true and admirable star in so many fields, but curiously I don’t think her delivery of that speech works in any version other than the first one. The one where it wasn’t this famous line being delivered practically like a quotation, instead where it was just a single line of dialogue in an hour script.

Specifically in Fame, season 1, episode 1, “Metamorphosis” by Christopher Gore.

Imagine writing a line that an unfathomably enormous number of people remember vividly, decades later.

Gore wrote the 1980 film, which is frankly better: it’s less about fame, more about failure, and it stands up very well. He also wrote the pilot episode for the series and I understand it went through a lot of changes before it even got to the draft script I’ve just read. The changes were all to help make a series out of a movie, and I don’t know how many other hands were involved.

Nonetheless, “Metamorphosis” is different to both the film and the rest of the series. I’d say there are three Fames – the film, this pilot script and then the rest of the series – but don’t get me started on how many versions there are. There’s also been a TV reboot, a film remake, and countless stage productions.

If nothing else, they surely milked that idea dry.

Only, as fond as I was of the show’s early years when I saw them in the 1980s and how I’ve mostly enjoyed reading – so far – 21 of the scripts – I think it’s an idea that ran out of milk really soon.

I wrote about Fame for the Birmingham Hippodrome a few months ago, just a couple of pieces for the programme for their production of the stage version. In one of them, though, I offered that the reason the series is remembered as being brighter and lighter than the film is that it had whole seasons to tell its stories, not just two hours.

That could have been true and certainly I convinced myself, writing that while deep in COVID. But now reading the scripts, seeing some episodes, Fame seems to be an archetype of a certain 1970s/80s US TV format that I don’t like. It’s the type usually described as having a reset switch. Huge emotional upheaval happens in an episode, but it’s all fine at the end. That kind of thing.

Not that Fame has really huge emotional upheaval in the series, but does land some very good moments and they are then forgotten.

Today we might still know a guest star is never going to be heard of again, but what happens in one episode of a series has an impact that lasts. I’ve always thought that was better than the reset switch, and I’ve always thought it for a dozen reasons, but this week I’ve got a new one.

The reset switch is meant to mean that everything goes back to normal at the end of each episode. But in effect, what that inevitably means is that every episode is starting from scratch next time. There’s no follow through, so there’s no momentum, so each time it’s right, let’s do it again.

I think that’s why Fame seems, to me, to struggle for stories very early on its run. Some episodes seem more forced than others, more “this’ll do” than anything else. Apparently there is one right toward the end of the run where the studio asked whether the producers really wanted to do this story and the producers said it’s this or it’s a two-week production shut down while we try to think of something good.

Still, even with a reset-switch Fame, you get episodes like “A Tough Act to Follow” by Virginia Aldridge where I haven’t got the script, I haven’t seen it recently, but I still remember its punch from 40 years ago.

So I’m not saying that a reset-switch series can’t be any good, I’m just now thinking that it is bloody murder to keep coming up with entirely standalone stories where you’ve got to take us from everything-is-peachy and on to everything-is-peachy-again. I don’t think you can raise the stakes as high when you’re being pulled down at the start and the end.

Curiously, there was one key series that famously and very noticeably ignored the reset switch. I’m sure there were others in the transition phrase between the 1980s and our present golden age of television drama, but one was noticeable because of its background and where its writers came from.

Star Trek: Deep Space Nine. If you’re thinking I couldn’t go further away from Fame if I tried, I see your point, but Deep Space Nine was the fourth Star Trek series and the preceding three were all primarily reset-switch ones. Very famously against the demands of the studio making it, Deep Space Nine kept on having good people do bad things and living with the consequences. There were consequences. They lasted throughout the run of the series, they weren’t tied off in a neat bow at the end of the hour.

And a key writer in making that happen, in even taking on his studios in protracted fights, was Ira Steven Behr. Yes. He wrote for Fame and then he showran Star Trek: Deep Space Nine.

Mind you, this week I learned that Fame’s showrunner, William Blinn, went on to write Prince’s movie, “Purple Rain”, and that now seems a bigger jolt.

I think I’ll shut up here, before I admit to you that in the 1980s, I had the most enormous crush on one of the Fame dancers. Phew. Nearly admitted that.

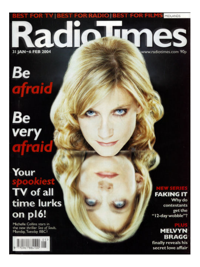

Flash forward to this week and on Tuesday I got to do it again, from my Birmingham office and over FaceTime audio. Two decades later, I am clearly the man in demand. But it felt like I was that day because 11 BBC Local Radio stations and 1 BBC national station wanted my opinion about the return of Fawlty Towers.

Flash forward to this week and on Tuesday I got to do it again, from my Birmingham office and over FaceTime audio. Two decades later, I am clearly the man in demand. But it felt like I was that day because 11 BBC Local Radio stations and 1 BBC national station wanted my opinion about the return of Fawlty Towers. I’m trying to see from your face whether you recognise any of that, but all I can see is that you’re looking a lot younger than me. I will try to still like you.

I’m trying to see from your face whether you recognise any of that, but all I can see is that you’re looking a lot younger than me. I will try to still like you.